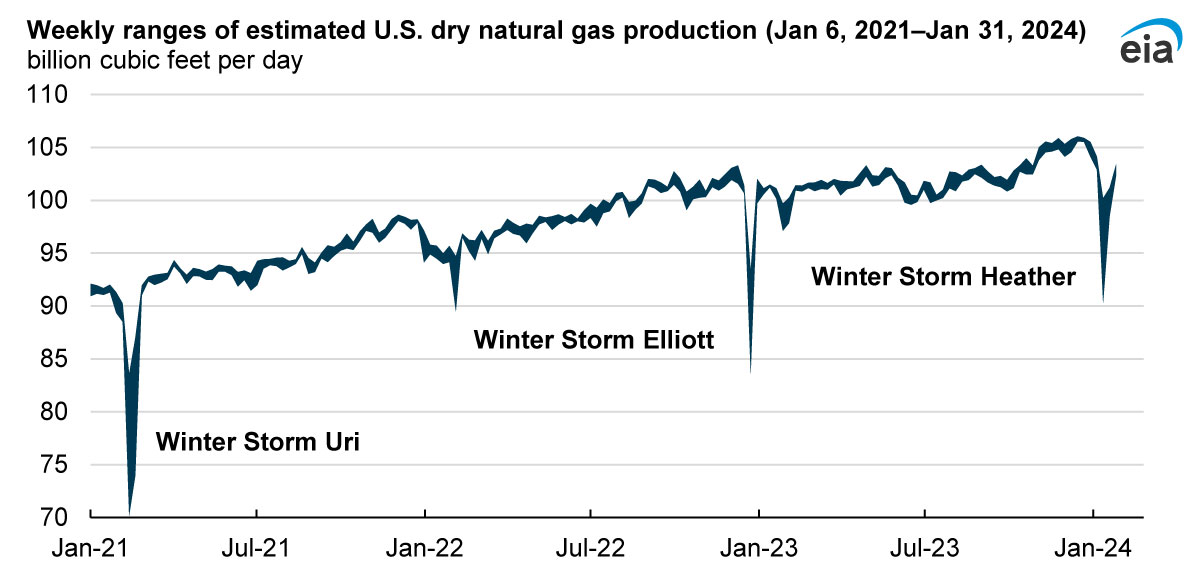

Over the last four winters, winter storms Uri (February 2021), Elliott (December 2022), and most recently, Heather (January 2024) interrupted weekly U.S. natural gas production by more than 15 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d), according to daily estimates from S&P Global Commodity Insights. These declines were the largest interruptions to U.S. natural gas production during the past four years. Although the impacts of these disruptions appear more muted over the course of a month, winter storms Uri and Elliott still drove declines in monthly average natural gas production of 3 Bcf/d to 7 Bcf/d.

Data source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, Short-Term Energy Outlook, March 2024

Note: January 2024 data point is an estimate.

Interruptions to natural gas production can occur at any time of the year in the United States and often vary in scale and impact. These interruptions can be caused by different factors, including inclement weather, maintenance events, or temporary oversupply conditions that cause a producer to reduce the volume of natural gas moving through a pipeline system. Severe weather that affects one or more of the major U.S. natural gas-producing regions, such as the Appalachia, Permian, and Haynesville regions, can cause noticeable levels of interruption on a national scale. These three regions combined accounted for 66% of U.S. natural gas production in 2023 and had accounted for 60% in 2022.

Regional production effects

Winter storms Uri, Elliott, and Heather affected U.S. natural gas-producing regions in different ways, depending on where the storms hit the hardest and how producers decided to adjust their operations to lessen the impact of cold temperatures.

Data source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

All three storms had a relatively large impact on the Permian Basin in West Texas and southeastern New Mexico. Some natural gas infrastructure in the Permian is not weatherized, so equipment is exposed fully to low temperatures and moisture in the winter. Winter Storm Uri in 2021 had the largest effect on Permian region production, reducing production by almost 5 Bcf/d in that region alone. In Texas, natural gas production declined almost 45% during Uri, and a severe disruption to the electricity grid caused power outages across the state that also contributed to some of those production losses. In August 2022, the Railroad Commission of Texas adopted the state’s first weatherization rule for natural gas facilities to protect natural gas flows to power generators in response to Winter Storm Uri. Winter storms Elliott and Heather decreased production in the Permian Basin by about 3 Bcf/d each.

Data source: S&P Global Commodity Insights

In the Haynesville region in northeastern Texas and northwestern Louisiana, both winter storms Uri and Heather contributed to natural gas production declines of over 2 Bcf/d. Most natural gas production in this region originates from newer wells in the Haynesville geologic formation, which contains relatively less water than other formations, making natural gas production equipment less susceptible to freezing.

In the Northeast region, which includes Appalachian Basin production activity, reductions in natural gas production during Winter Storm Elliott in 2022 were much larger than the declines during winter storms Uri and Heather. Because below-freezing temperatures are more frequent in the Northeast, producers tend to install additional equipment to lessen the challenges of cold weather. However, temperatures fell below 0°F in many parts of the Northeast region during Winter Storm Elliott, reducing natural gas production volumes by over 6 Bcf/d. During the storm, temperatures in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, declined to as low as -5°F on December 23, 2022, a record low for that day.

Production interruptions

Interruptions in natural gas production typically include various individual producer actions at wells, gathering systems, and transportation networks. Some producers temporarily and pre-emptively suspend production, often before adverse weather or maintenance work that is likely to reduce the natural gas takeaway capacity of a distribution system.

Other production interruptions are involuntary. Freeze-offs can occur when water or hydrates (crystals containing water and hydrocarbon molecules) in the natural gas stream freeze at a lower temperature or pressure, which creates blockages and disrupts the flow of natural gas from a well or through a natural gas transportation system.

Freeze-offs can also occur when:

- Ice forms on equipment or on moving parts of the natural gas transportation system, which can block automated controls from functioning properly or cause valves or other equipment to freeze closed or open

- Freezing temperatures cause power outages that prevent natural gas equipment from functioning properly

- Snow or ice prevents worker access to key equipment rooms or production spaces that control production

Production interruption prevention

Producers often attempt to prevent freeze-offs within the natural gas stream by injecting methanol or other chemicals into the natural gas stream to lower the freezing point of the water in the stream, reducing ice blockages. Producers and transportation operators can place compressors and machinery into enclosures or underground to avoid direct exposure to the cold air and moisture to help prevent freeze-offs. They can also use other methods, such as air dryers, windbreakers, temperature monitors, pipe insulation with built-in heating cables, and portable heaters or line-thawing machines.

Despite these efforts, severe winter weather still causes issues, and producers generally voluntarily interrupt production to avoid events that might cause damage to equipment or force natural gas in blocked pipes to be vented into the atmosphere. Although a voluntary shutdown stops production for a short time, from a few hours to a few weeks, the natural gas production is not completely lost. The natural gas in temporarily shut-in wells remains in the wells until production begins again. Immediately after restarting production, these wells often produce more natural gas than before the shutdown because of a temporary pressure build up.

Follow us on social media: