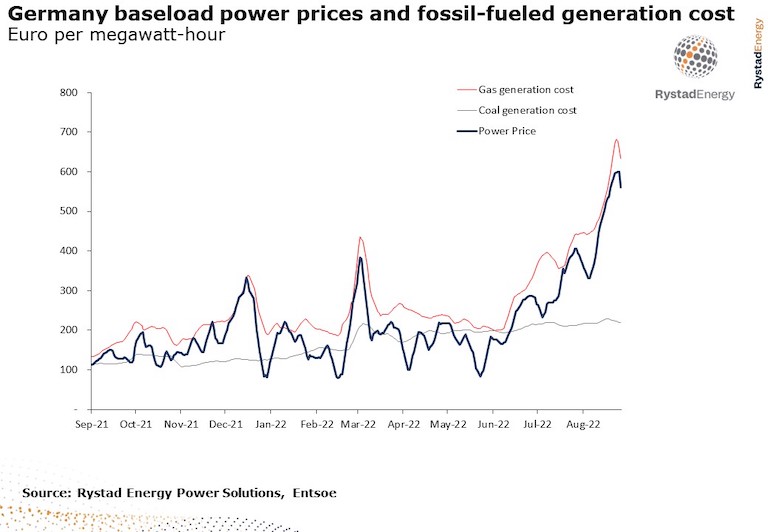

The European energy sector continues to be shocked by price volatility and uncertainty over energy balances for the coming winter. Power spot prices across Western Europe have climbed to unparalleled levels: daily average prices have traded above €600 ($599) per megawatt-hour (MWh) in Germany and above €700 per MWh in France, with peak-hour spikes as high as €1,500 per MWh. Now there is a risk of even higher prices during the winter months as Russia has halted all gas exports through Nord Stream 1 for an indefinite period. However, the European Commission is still exploring alternatives to limit the impact of extreme prices for end users. Strong volatility in the gas market is the cause of these fluctuations, as some signals switched from bearish to bullish over the weekend. The market is also unsure how to react to the proposed EU market intervention, where one target seems to be capping gas prices and another decoupling the European gas and power markets. Rystad Energy research shows that if gas demand has to be reduced, as seems increasingly likely, Europe will face a series of unenviable options – from cutting power to industry to rolling blackouts for consumers.

Recent price rises have been caused by a perfect storm of lower Russian gas supplies; nuclear outages; and low hydropower generation and coal supply disruptions because of drought. Of these factors, lower gas supplies have the greatest effect because gas continues to be needed in the power mix and is the marginal source of supply and therefore hits prices the most. However, the historically high gas prices have so far not curtailed demand from the power sector significantly – which means tougher measures may be needed. EU member states last month committed to voluntarily reducing their gas demand by 15% from 1 August through March next year in case of supply shortages.

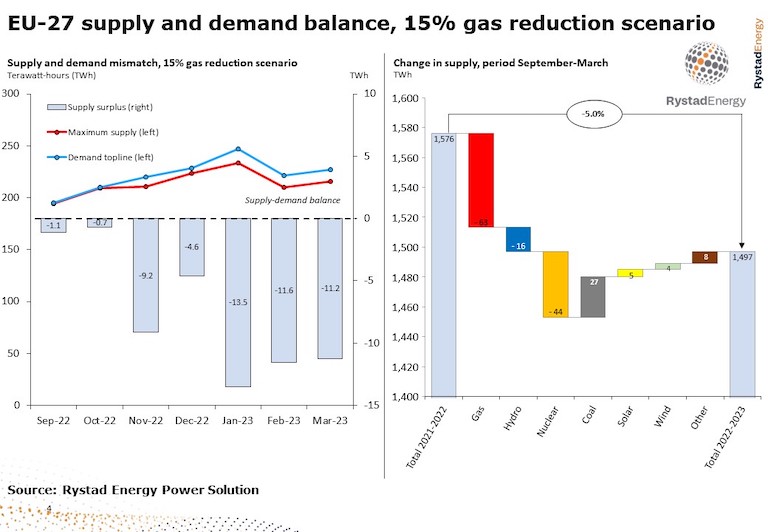

If these 15% demand cuts become mandatory within the EU, an imbalance in power supply and demand could appear as soon as this month and worsen into 2023. The power deficit is estimated to reach a maximum of 13.5 TWh in January before gradually being reduced. A straight 15% gas-for-power demand cut is not the most likely, however, as other sectors such as industry would likely face a higher reduction to shield the power sector to ensure security of supply. A worst-case scenario with very cold weather, low wind generation, and a 15% cut in gas-for-power demand would prove very challenging for the European power system, and could lead to power rationing and blackouts.

Gas continues to be needed in the power mix

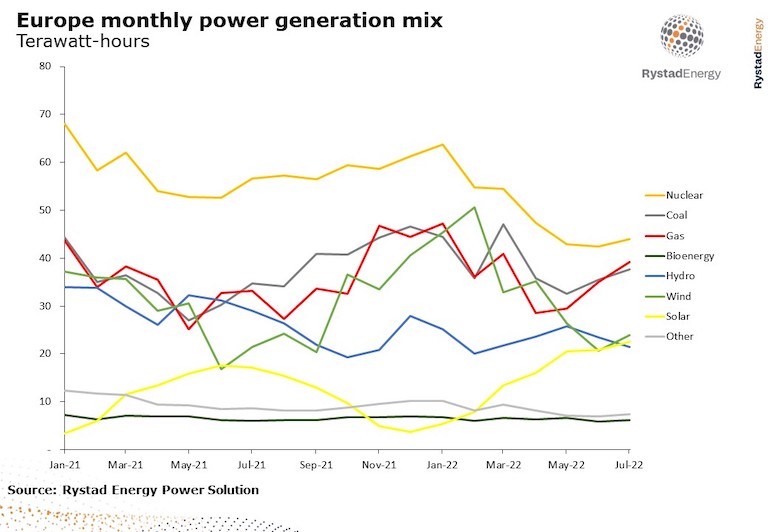

European utilities are, despite great efforts, struggling to reduce their dependence on gas – in fact, gas-power generation has climbed as a result of the challenges mentioned above. Nuclear and hydropower generation in the EU have dropped 14% and 25% year-on-year, respectively, erasing 110 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity supply from the grid. This has been compensated by higher wind, coal, solar and gas generation. Overall, gas-power generation has grown 6% year-on-year to reach 39.1 TWh in July. Things will get even more challenging towards the end of the year as seasonal electricity demand increases – electricity consumption in December is normally 25% higher than in July, meaning that European consumption could reach more than 280 TWh per month.

“Regardless of the exact scenario, the coming winter is certain to be the most challenging Europe has seen in decades – and consumers or governments are expected to pay the price. If gas demand needs to be cut, we expect to see power supply issues emerging this month and worsening into 2023,” says Carlos Torres-Diaz, head of power at Rystad Energy.

Russian gas supplies have dropped 89% and could fall further

In the first half of last year, Russia exported close to 350 million cubic meters per day (MMcmd) of natural gas to Western Europe through its main export routes. Flows have dropped below 40 MMcmd in recent days, down 89% year-on-year. Most of this decline has been the result of a halt in flows through Nord Stream 1 related to technical problems, though political issues related to the war in Ukraine are also widely believed to play a part. Flows through Poland and Ukraine are also down. Russia’s Gazprom halted all exports through Nord Stream 1 from 31 August. Although flows were expected to resume after a three-day maintenance in the remaining compressor, Russia has now stated that flows will not resume in full until sanctions are lifted. This latest move has significantly increased the risk that Europe may not get further gas flows through Nord Stream 1 for the whole winter.

Alternative power sources to replace Russian gas

In a scenario where the EU’s efforts to reduce gas use results in total EU gas-for-power demand being cut by 15% compared to the five-year average, the lost supply – corresponding to about 5.5 TWh per month – would have to be replaced by other sources, demand reductions, or increased power imports into the bloc. As seen in Figure 2, power generation from hydropower and nuclear has dropped sharply this year, while coal, gas, solar and wind have all increased. To estimate whether a 15% reduction in gas power generation is realistic for the coming months, we need to look at trends so far in 2022 and for the past five years. As mentioned, coal power generation has jumped 12% year-on-year across the bloc this year, and there is some room for additional utilization if needed in December and January. Load factors have been higher than normal so far this year, but can still rise further to the historical highs of around 70% for the fleet as a whole.

Hydropower generation, on the other hand, has plummeted 25% so far this year. Water levels in Europe normally reach their maximum between the second and third quarters of the year, which means reservoirs are unlikely, given the region’s low rainfall levels, to recover from their record-low levels before the winter. Hydropower generation is therefore expected to remain low for the next six months.

Nuclear generation is down 14% in the EU so far this year, and the outlook is bleak. France’s EDF is striving to bring back online the nuclear reactors that are currently under maintenance for the winter. Their restart dates are still uncertain so current low generation levels could be expected. Solar and wind generation are both massively up this year – by 25% and 14%, respectively – boosted by particularly large capacity additions. Growth assumed for the remaining months is in line with capacity additions that could total 25 gigawatts (GW) for solar and 15 GW for wind in 2022 – an increase of 16% and 8%, respectively, year-on-year.

Higher generation from coal, solar and wind power could help partially cover the drop in gas supplies by adding an additional 34 TWh in the period September to March 2023. However, this would not be enough to make up for the shortfall from gas, nuclear and hydro generation, which means additional measures would be needed. European electricity demand has shrunk 2.2% so far this year, mostly because the record-high prices have reduced demand, particularly from the industrial sector. Continued high prices are likely to keep demand at the current low level or push it even lower. A similar year-on-year drop of 3% during over the coming months is feasible, not only as high prices affect industrial and household consumers, but also as a result of electricity-saving measures rolled out by governments.

We have created a full scenario for power supply and demand, assuming a 15% reduction in gas-for-power demand, additional supply from coal, solar and wind, and lower overall electricity demand (see above figure). This shows that an imbalance in supply and demand could emerge already this month and worsen going into 2023. The deficit reaches a maximum of 13.5 TWh in January before falling gradually. This scenario indicates a total power deficit in the EU of 51 TWh for the full period from September 2022 to March 2023, which will have to be made up by additional imports from Norway, the UK and Switzerland, or other neighboring countries. The deficit can also be reduced by cutting total demand. If so, demand would need to decrease by 5% from the year-earlier period.

Our analysis shows that the power generation balance in Europe is severely challenged in a scenario where gas supply is significantly reduced, because there is not much flexibility to ramp up considerably from other sources. Any other alternative would require a large decline in power demand. As mentioned, demand has already dropped about 2% so far this year – but expanding this to a 5% reduction would appear a stretch. In addition, gas is by far the most flexible source of supply in Europe, helping balance supply and demand in periods with large variations in solar and wind generation, for example. It would be challenging to get this flexibility from other sources such as nuclear or coal.

Follow us on social media: