Wind plant performance—how much electricity a wind plant generates compared with its maximum possible generation—depends almost entirely on the availability of wind resources, which vary depending on both the time of year and the geographic region.

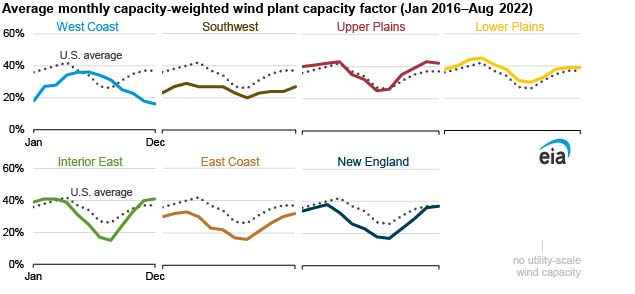

The performance of a power plant is often characterized as a percentage of the maximum possible generation in a given time period, a metric known as capacity factor. Nationally, between January 2016 and August 2022, wind plant capacity factors peaked in March and April and were at their lowest in July and August.

Unlike fossil fuel-fired power plants, such as coal or natural gas plants, wind plants don’t incur any fuel costs to generate electricity, so the electricity they produce is almost entirely determined by available wind resources. Wind plant performance is influenced not just by wind speed, but also by wind direction, wind constancy, and turbine height.

Because of geographic differences in wind resource potential, wind generation varies across regions. We grouped states into regional groups that have similar wind capacity factor patterns. The Lower Plains region of Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and New Mexico has the largest share of U.S. wind capacity, at 44% as of August 2022. Because of the concentration of wind capacity in the Lower Plains, the national wind performance pattern follows the seasonal wind performance pattern of the Lower Plains quite closely: performance peaks in the spring, declines in the summer, and rises again in the fall and winter.

The Upper Plains region has the second-largest share of U.S. wind capacity, at 29%. The Upper Plains also generally follows the same seasonal pattern as the Lower Plains.

The Interior East region (13% of U.S. capacity) follows that same pattern but with a steeper decline in the summer months than the Lower and Upper Plains.

The seasonal pattern is quite different in the West Coast region (10% of U.S. wind capacity), where the pattern is driven largely by a concentration of wind capacity in California. Wind capacity factors in the West Coast region rise later in the spring and peak in the summer months before steadily declining into the fall and winter. This pattern results from the cold air of the Pacific current interacting with the sea breeze as well as the location of California wind plants, which are generally close to mountain passes near the coast.

In the Southwest, East Coast, and New England, capacity factors were slightly lower than the national average, and they have fewer wind plants. In total, these three regions made up 4% of the country’s wind capacity as of August 2022.

We publish data on capacity, generation, and capacity factor at the national level in our Electric Power Monthly. We publish state-level statistics in our State Electricity Profiles. Many data series are also available in our Electric Data Browser.

Follow us on social media: