Governments and institutions around the globe are seeking immediate fixes and long-term solutions to the ongoing energy crisis, exacerbated by the ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine. Mainland China, already in pole position in terms of access to critical raw materials (CRM) and processing, is relaxing regulations to encourage energy intensive companies to relocate, while the Inflation Reduction Act in the US at the end of last year offered simple tax breaks enticing companies to set up shop in the country. Amid a push to retain its lead in the energy transition, the EU must do more than just play catch-up to secure sustainable energy to its citizens, and the worlds largest single market.

Rystad Energy analysis shows that the EU plans to deploy targeted anti-relocation measures, largely through a simplified regulatory framework and financial support mechanisms to accelerate deployment of clean tech. This may be enough to turn the tide, as regulatory bottlenecks and underdeveloped supply chains have held back clean tech development for years and now put the EU at a competitive disadvantage. We expect direct financial support, centralized one-stop shops for permitting and designated go-to areas for fast-tracked renewables development will contribute to accelerating the EU’s energy transition, but this will only be as effective as the administrative capacity allows.

In the battery and electric vehicle sector, which is the most contentious point between the EU and US, Rystad Energy believes that reducing administrative delays for battery supply chain projects may not be enough, and the EU could need to push forward all pillars in parallel. Although Europe has an existing and growing market base, the likelihood that the US increase its presence in the market has never been higher.

When it comes to green hydrogen, Rystad Energy analysis finds that the EU has high domestic production targets but has a long way to go to get there. To manage the risks of the US kickstarting its low-carbon hydrogen industry via simple production tax credits, the EU aims to provide a fixed premium for hydrogen production – however, as the proposed auction mechanism is bid based and will happen in increments, it may be too little too late.

To accomplish these goals, it is crucial for the EU to first secure access to CRMs and, second, foster industries to turn CRMs into clean tech. In this regard, CRMs are the oil and gas of the energy transition, and against the backdrop of the ongoing war in Ukraine, the EU sees a similarity between Russia’s use of energy as a weapon and a CRM supply squeeze potentially being used to hinder its energy transition. This comes as the EU depends on China for CRMs, and should Chinese policy become more protectionist, the EU would have to either stand on its own, lean on other trade partners, or fall short of meeting its ambitions.

“Europe has always been an importer of energy, so the energy transition offers an unparalleled opportunity for the EU to flip the switch and secure its energy sovereignty. However, the EU finds itself between China’s existing market dominance and the US’ fiscal firepower. We believe that the EU could use its clout as the single largest market in the world, as well as the Green Deal Industrial Plan, REPowerEU and other policy levers to earn its energy security, and become sustainable in the process,” says Lars Nitter Havro, senior analyst, clean tech at Rystad Energy.

Green Deal Industrial Plan four pillars explained

Nevertheless, for the EU to meet its climate targets, simply ensuring a robust supply of CRMs is not enough. The EU will also need to speed up slow decision-making processes, while being able to originate, scale and retain businesses across the clean tech value chain is an urgent priority for the bloc. To manage these risks and turn the tide, the EU Commission in a 1 February communication presented the Green Deal Industrial Plan (GDIP). EU member states will discuss the GDIP proposal at a meeting in Brussels on 9 February and, based on their input, the Commission will develop a more formal proposal to be presented at the European Council in March.

The GDIP consists of four pillars. The first aims to facilitate a conducive regulatory environment that enables fast upscaling of crucial clean tech sectors, including via the Net Zero Industry Act and the Critical Raw Materials Act. The Net Zero Industry Act will stipulate 2030 targets for the EU’s clean tech industry, focusing on supply chain investments and regulatory simplification to speed up slow permitting processes for industries such as renewables and energy storage. The Critical Raw Materials Act will look to ramp up mining, refining, processing and recycling of CRMs in the EU, establish a Raw Materials Club with similarly minded governments, and break down the existing monopoly held by China. Through the Critical Raw Materials Act, the EU may propose objectives such as a 30% self-sufficiency target on CRMs, and to recover at least 20% of rare earth waste streams in the medium term. Incremental increases of such targets are expected in the medium term. We expect it will also seek to maximize recycling capacity to lower import dependency and production requirements.

The second pillar – funding and state aid – seeks to counter relocation risks by providing competitive offers and incentives such as tax breaks (for example, to level the playing field with the Inflation Reduction Act). This may entail temporary acceleration and simplification of state aid rules via the Temporary Crisis and Transition Framework to enable faster approvals, and likely include tax break models and targeted aid for clean tech value chains. In addition, provisions may also include the EU matching subsidies offered by countries outside of the EEA for clean tech development. Given the current financial environment, however, not all member states are showing support for increased borrowing and would rather see existing funds spent. For instance, a group of countries led by Germany are fighting to turn to the €723.8 billion ($786 billion) raised through the post-Covid-19 pandemic Recovery and Resilience Fund of grants and loans. We expect the EU to redirect this fund towards tax credits but also move to raise additional funds to support clean tech investments. The state aid approach will only work for a few of the EU’s largest economies, meaning that the bloc will likely prepare a European Sovereignty Fund as part of its mid-term Multiannual Financial Framework in the second quarter of this year. The key argument for the fund is to level the playing field among member states and avoid an unfair subsidy race through increased funding for research, innovation and strategic industrial projects.

The third pillar seeks to ensure that European skills can grow in parallel with the clean tech transition, from finance and regulatory sectors through to manual labor. One of the key means of doing this is to have an active industry that requires capabilities from research and universities to operation of assets. This is crucial and will take years to fully develop.

The fourth pillar sets out to deliver resilient, international supply chains through trade agreements. As the energy transition accelerates and emerging markets such as Africa and South America mature their clean tech sectors, finalizing ongoing trade deals (New Zealand, Chile and Mexico) will be essential. Completion of the Mercosur Trade Agreement (a South American trade block consisting of Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay) will also be crucial for the EU. Importantly, the EU also sees continued nurturing of trade relations with the US in light of the Inflation Reduction Act’s impact on trade dynamics to be essential and is eyeing synergies rather than looking for a subsidy race. In addition, the EU considers foreign subsidy regulations and other tools to counter China’s perceived use of unfair trade practices.

Fundamentally, the four pillars are geared towards accelerating the deployment of three key energy transition industries: renewables, batteries and hydrogen. Renewables sit at the crux of decarbonization – however, without batteries, bringing the power and transport sectors to net zero will be impossible. In addition, for Europe’s large hard-to-abate sectors, such as steel and shipping, hydrogen will be the fulcrum that enables decarbonization.

EU bets on simplified regulatory framework and financial support to accelerate renewables

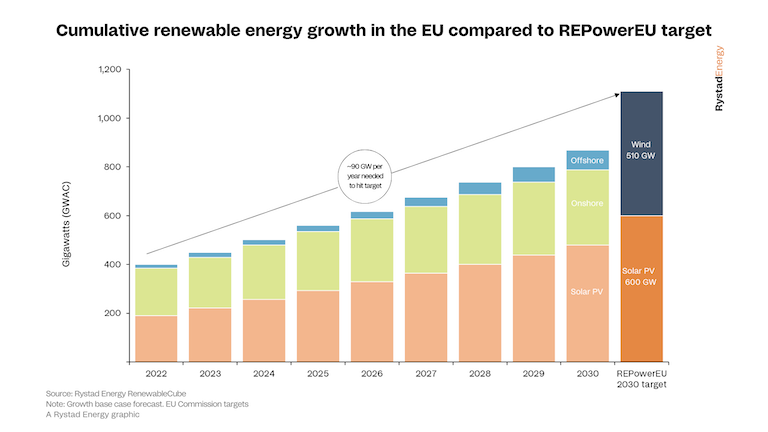

Hit by the energy crisis, EU legislators spent 2022 negotiating the REPowerEU plan, aiming to reduce dependency on Russia and accelerate the energy transition. Although still to be approved by the Renewable Energy Directive (RED IV), the proposal led to an increase in the renewable energy target for 2030 from 40% to 45% of total energy supply and hitting 600 gigawatts (GW) of installed solar PV capacity by the end of the decade. However, the plan does not include concrete measures. We currently forecast 870 GW of installed wind and solar PV capacity by 2030, although 1,100 GW would be needed to meet targets. The EU therefore needs to accelerate its commissioning rate from the current 59 GW per annum to 90 GW per annum. The key issues to address include administrative and supply chain bottlenecks, lack of skilled labor, dependence on imported raw materials, inflation, grid issues and lack of concrete financial incentives.

As other countries have introduced strong incentives, the region’s competitiveness in the renewables market is threatened. China raised concerns with its latest five-year plan designed to further boost its domestic industry with heavy subsidies and entice European energy companies to relocate. In addition, the Inflation Reduction Act in the US is highlighting the importance of dedicated production and investment tax credits for clean technologies. The Act provides long-term support for renewable energy developers – which we estimate could result in an additional 155.5 GW of onshore wind and solar PV capacity by 2030 – and is likely to support the US solar PV manufacturing industry through advanced manufacturing production credits (section 45X). Based on our research, this could spur domestic capacity from 25.8 gigawatts-direct current (GWdc) today to 78.9 GWdc by 2025. As such, a major risk the EU is facing is that start-ups will kick off in the US rather than within its own borders.

There are three main levers for the EU to retain its renewables industry: de-risking disruptions from other markets; solving historical bottlenecks through a predictable and simplified regulatory framework; and setting up dedicated financial support. While the Inflation Reduction Act could disrupt transatlantic trade and investment, the EU aims to allow its domestic industry to benefit and enhance EU-US collaboration. It is unclear at present how European firms could potentially be exempt from the Inflation Reduction Act regulations in the US, but if it were to happen, it would only be a temporary solution as companies would eventually have to relocate to the US after 2025 to meet the conditions set out under the regulations. In the case of China, the EU sees it as essential to reduce the risks of unfair practices against EU companies through means such as Foreign Subsidies Regulations, or even formal investigations, but without breaking ties with what is a key partner.

To address regulatory bottlenecks and supply chain challenges, which for years have remained the largest hold-up to renewables development in Europe, the EU proposed the Net Zero Industry Act. With dozens of gigawatts stuck in administrative procedures, the EU acknowledged that current permitting delays are incompatible with its ambitions and adopted an 18-month Council Regulation to speed up the process, notably by requiring member states to design ‘go-to areas’ where permitting should not take longer than one year for renewables projects and two years for offshore wind projects. While these measures may have a short-term impact on the market, it is essential the EU extends these long term to provide developers with security like that of the 10-year Inflation Reduction Act. As part of the GDIP, the implementation of centralized ‘one-stop shops’ for permitting is expected, which would help streamline the process if adequate administrative capacity is available. This will speed up renewable energy deployment, thus requiring the EU to accommodate faster grid expansion, which may also be necessary to include in the GDIP. As the EU will propose its reform to the electricity market design to lower costs for consumers through increased use of renewables, it must be cautious not to discourage investment as was done with the temporary revenue cap.

When it comes to supply chain bottlenecks, Europe is facing growing challenges, especially for solar PV and wind. China dominates the entire solar PV value chain, from polysilicon production to cell and modules manufacturing. The EU has acknowledged the challenge by launching the European Solar PV Industry Alliance – however, financial instruments to increase production capacity as well as to enhance skills have yet to manifest. In addition, the wind industry supply chain, having suffered from inflation, needs similar support to recover supplier margins and competitiveness. We expect the GDIP anti-relocation measures for the renewable energy supply chain sector in the form of direct financial support, simple tax break models, tax credits or even accelerated depreciations will likely strengthen the EU’s position and reduce the risk of relocation.

EU focused on reducing administrative delays for battery supply chain projects

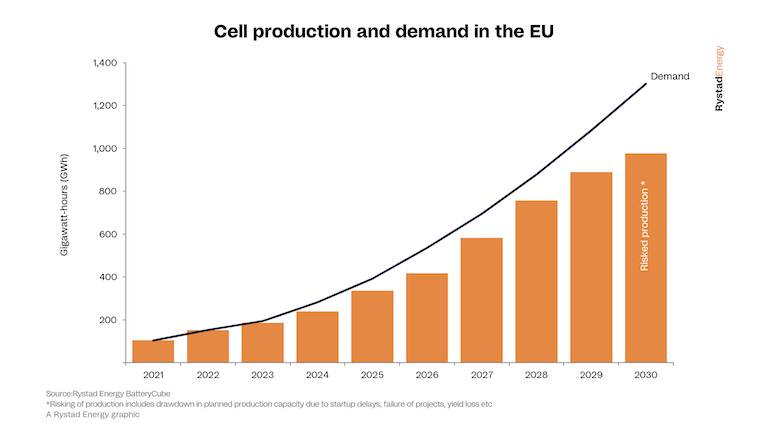

Batteries will play a key role in the EU’s quest to fully decarbonize its transportation sector and to meet the growing energy storage demand for its renewable energy ambitions. The EU aims for all new car sales to be electric vehicles (EVs) by 2035, while the US has a 50% EV market share goal by 2030 – however, the race to electrify transportation is not only driven by targets. The Inflation Reduction Act has fundamentally shifted the dynamics of the EV market.

The EV supply chain ranks second on the Act’s funding list, with $23 billion allocated to transportation. This includes purchase tax incentives for consumers of up to $7,500 per vehicle, and production tax incentives for cell and battery manufacturers. For funding access, however, EV companies must source at least 40% of the CRMs used in battery production from the US or a country that has a US trade agreement (with the threshold increasing to 80% by 2026). Secondly, the battery components must be manufactured or assembled within the US, Canada or Mexico, with the requirement increasing to 100% by 2029. These conditions are expected to drive companies to relocate to the US or establish integrated supply chains within the country to continue to receive subsidies beyond 2025.

The requirement to purchase US-made vehicles to benefit from these tax breaks and the lower energy prices in the US have already prompted companies such as Tesla, Iberdrola and Safran to move some of their operations to the US. Volkswagen, which bet heavily on European cell maker Northvolt, is already eyeing investment opportunities in Canada to receive the maximum tax credits. This implies that tier-one investments are being redirected to North America, putting the EU supply chain at risk.

Despite the restrictions of the Inflation Reduction Act to receive tax credits, the untapped potential for the country’s EV market is a major reason for its attractiveness. Over the last five years, the US market alone has sold more passenger vehicles (EVs and internal combustion engine vehicles) than the EU. Further, the EU market had an EV share of 21% in 2022, while the US had a market share of 6.5%. We expect this will push automakers to comply with these restrictions, cementing the supply chain firmly in North America.

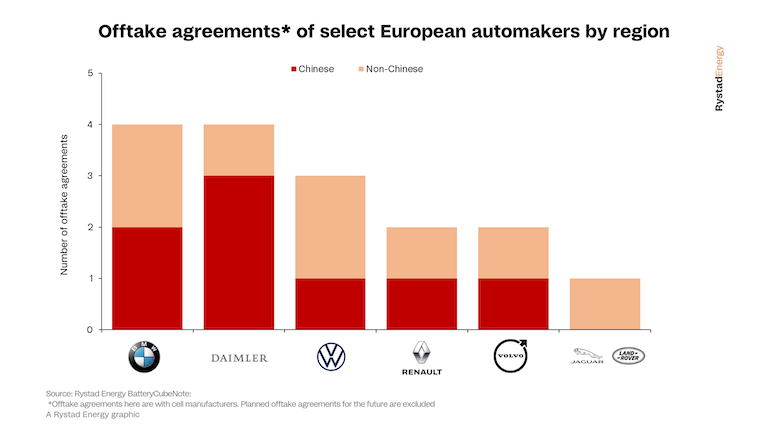

As is the case for the GDIP, the Inflation Reduction Act tax credit restrictions are put in place to remove dependency on China in the battery supply chain. Glenn Youngkin, governor of Virginia, announced the state would not be competing as the location for Ford’s planned facility in the US because the plant is to be operated by Chinese cell maker CATL. US automakers, however, have several partnerships in place already with Japanese and South Korean cell manufacturers that allow them to attract investments from automakers and plan joint ventures with non-Chinese cell suppliers. European automakers, meanwhile, have largely been reliant on Chinese suppliers for European distribution, and offtake agreements struck with non-Chinese suppliers are mainly for businesses in the US.

Continued Chinese reliance is not reflected in the current trend, where planned offtake agreements of European automakers involve a variety of European cell manufacturing start-ups. However, offtake agreements have been a problem for European cell manufacturing start-ups. For instance, the UK government pledged £100 million ($121 million) in funding if Britishvolt – which has since collapsed – reached certain milestones. Comparing the funding size, it is not far from the €155.4 million that peer Northvolt had from the German government. While there are many reasons that let to Britishvolt’s collapse, not being able to secure a long-term deal with automakers was the hard stop. Supportive policy is key here, and many major global economies have been adopting legislation to stimulate offtake. The fall of Britishvolt is a major lesson for the EU and its policy makers – because of the lack of support from the regional supply chain, the company stood little chance against the global battery materials leader, China.

The EU’s battery future currently faces two challenges:

· Attracting investment into EU companies is difficult due to an underdeveloped battery supply chain, as well as higher energy and labor costs. Encouraging and incentivizing more renewable energy projects would help bring manufacturing costs down. REPowerEU is the first step towards this.

· Chinese companies entering the market, such as CATL in Hungary, is happening because of internal economic disparity in the EU. Developing a stable local battery supply chain would require member states to present a united front.

Foreign investments in the EU have largely been led by offtake agreements. This can be capitalized on further by providing tax benefits to the automakers that sign agreements with local cell manufacturers. Since top tier cell makers are relatively agnostic in terms of tier 1 and 2 manufacturers – and instead focus on acquiring sustained cell supply (for example, Volkswagen is set to secure cells from Northvolt and CATL) – this can prove to be an excellent opportunity for the EU to incentivize local clusters, much like North America has. These cell manufacturing start-ups, in turn, would raise capital and ensure they do not fail. This must be followed by ensuring there is no additional bureaucracy or delays to projects that could force automakers to choose consistent supply over subsidized cells.

Overall, the EU finds itself in a precarious position when it comes to the EV and battery industry, given the demand for batteries to further its net-zero ambition and the need to set up a local supply chain. But alienating China would be detrimental to its ambitions, meaning most likely some concessions will be made by both parties to ensure cooperation on the EV front. With the final proposal for the GDIP in place, member states will aim to set targets for production capacity up to 2030 based on battery demand, and the ‘one-stop shop’ is a positive effort to reduce permitting delays. InvestEU, which currently supports two battery projects worth a combined €162 million, will see more funding for projects between 2024 and 2027. Also, the Innovation Fund will see a competitive bidding process for battery production, and instead of taking on 60% of a project’s expenditure, will introduce production subsidies.

EU to counter Inflation Reduction Act with green hydrogen auction for domestic production

With the EU steaming towards a hydrogen economy, a strong supply chain that can support the upcoming demand for fuel cells and electrolyzers will be critical. Although the demand is expected to mature in the medium to long term, being proactive and securing key competencies to hedge the costs that may emerge from postponing any development will be strategically significant. The EU has already been a front runner in the hydrogen race, with extremely aggressive targets set under its REPowerEU push. The ambitious goal is 10 million tonnes per annum (tpa) of domestic production and 10 million tpa in hydrogen imports. As of the end of 2022, the risked pipeline of projects in Europe alone amounted to around 9.2 million tpa within 2030, out of which the EU27 accounts for 7.8 million tpa. This is just 2.2 million tpa shy of the EU’s 2030 target.

That said, the US leapfrogged the EU with its aggressive Inflation Reduction Act credits including a production tax credit that can give developers up to $3 per kilogram of hydrogen. While there are still some unknowns, the simple credits in the US have triggered investors and companies to move across the Atlantic. The EU’s previously planned business incentives to boost continental hydrogen production were complicated but the recent communication from the Commission is aiming to change this. Instead of a complex and slow contract-for-difference (CfD), it intends to provide a fixed premium per kilogram of hydrogen, similar to the Inflation Reduction Act. Unlike the US Act, however, the EU will be more budget conscious by selecting projects from an auction with an initial budget of €800 million. The CfD and the European Hydrogen Bank remain on the horizon after this fixed price support.

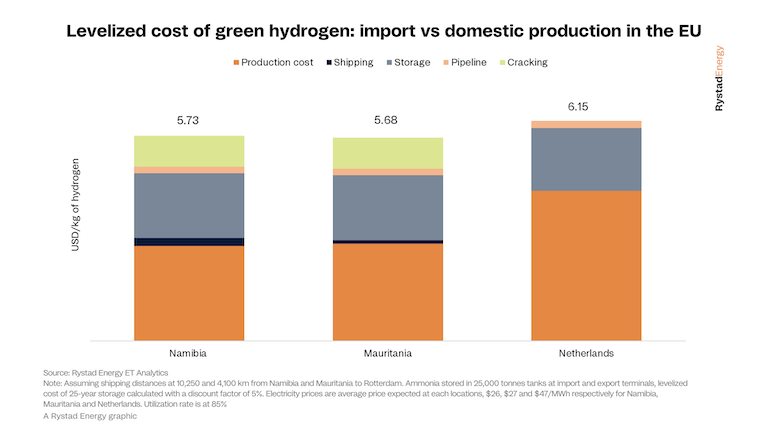

The domestic supply only solves half of the target, and the EU is already working on forging trade ties with nations in Africa and the Middle East as well as with Australia, which are all slated to become key exporters on the back of their abundant renewable resources. To this end, we have assessed the viability of importing green hydrogen from a purely economic perspective. Our estimates show that the cost of importing green hydrogen via hydrogen carriers (such as ammonia and cracking it back to green hydrogen at point of use) may be more favorable than domestic production. As no operative large-scale cracking facilities currently exist, costs are modelled on smaller-scale projects – but large-scale projects are under way in several areas, such as Rotterdam, and we expect costs will come down substantially within the next four to six years. Cracking aside, importing green ammonia can be significantly cheaper than producing it in the EU and efforts have been made to develop the direct use of ammonia in many segments beside fertilizers and chemical industries – for instance, green ammonia is expected to be one of the largest offtake sectors of green hydrogen in the EU as a zero-carbon shipping fuel.

Despite potentially favorable import economics, domestic green hydrogen production will still play an important role as EU renewables could help produce it from excess offshore wind (and avoid curtailment) or abundant renewable resources in Southern Europe. Access to raw materials supply will be key to supporting the growth of a domestic hydrogen industry. As the EU has high dependency on raw materials for electrolyzer production – and with the most recent EU report on CRMs noting it has less than 1% of the required assembly supply chain for fuel cells – it will be crucial that the bloc ensures trade routes with economies rich in hydrogen-relevant CRMs, such as South Africa, which is a central player in the hydrogen CRM supply chain.

Follow us on social media: