Oil tanker tycoons are enjoying a surge in revenue as the sanctions triggered by Russia’s war are redrawing the global trade in crude. And it’s set to last.

The disruption is fairly simple. Europe, for decades the top buyer of Russian oil, is banning purchases from Moscow next month and has already been cutting back. Those cargoes are instead flowing out to Asia. The result is ships sailing thousands of miles further, driving up a vital aspect of demand.

“I can’t say that I have seen a trade disruption before on the scale we have now,” said Halvor Ellefsen, a supertanker broker at Fearnley Shipbrokers UK Ltd., who’s worked in the industry since the 1980s. “This time, I think it’s a paradigm shift whereas previous geopolitical events have tended to be short lived and back to normal more quickly.”

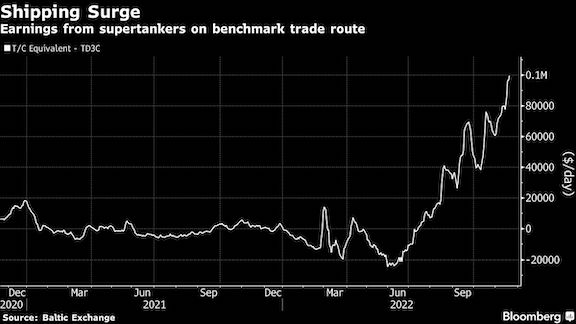

A key industry gauge, ton miles, which is the volume of cargo transported multiplied by the distance it sails, is expected to increase by 4.3% this year, according to Clarkson Research Services Ltd., a unit of the world’s largest shipbroker. Daily earnings for the industry’s largest supertankers reached $99,628 on Friday, four times the average of the past four years, on the market’s benchmark route.

The freight market will remain strong for 2023 and 2024, mainly due to “structural” changes to trade flows, said Frederik Ness, an analyst at SEB, “The most important driver is that the changes to trade flows are sticky.”

Cargoes that were routinely being transported across the Baltic Sea to reach the North Sea port of Rotterdam are now sailing to India and China, comfortably twice or three times the distance.

“The new trading routes developed from the war have been a tremendous uplift to an industry where capacity gains have been de minimis for most of this year, and will continue to be for the next couple years,” Jon Chappell, senior managing director at Evercore ISI said.

Added Pressure

With oil demand expected to increase next year and inventories in developed nations at an 18-year low countries may become more reliant on imports, said Omar Nokta managing director and lead shipping research at Jefferies LLC. That will place further strain on the tanker industry to deliver them.

It’s unlikely that there will be any respite from rising freight costs in the form of more transportation capacity, as the age of the tanker fleet is steadily rising, boosting the pressure to scrap. The average vessel was built 12 years ago, meaning the fleet is the oldest since 2004, according to Clarkson data.

Vessels are normally delivered two years after they’re ordered, and the order book for new ones is close to an all-time low, said Lars Bastian Østereng, a shipping analyst at Arctic Securities ASA. Usually, tankers are recycled after 20-25 years or so, but given its age, the tanker fleet is going to shrink if that happens now, according to Østereng.

Place Bets

Ness estimates VLCC rates will rise to $56,000 a day in 2023 and $60,000 the following year. That’s up from an average of $33,000 over the past decade.

This winter though, Nokta says rates of $100,000 a day are well supported and likely to rise to between $150,000 and $200,000 a day. He, too, is estimating that the market will stay stronger for longer.

Europe’s sanctions come into full force on Dec. 5, after which time the bloc will have to halt seaborne imports almost entirely, causing the chaos in trade routes to deepen.

“The tightness of supply, the run-up to the Dec. 5 deadline, the seasonality -- it’s all pointing in the right direction,” said Brian Gallagher, head of investor relations at Euronav NV, one of the world’s largest owners of crude-oil tankers. “We do genuinely believe that there’s a longevity to it all.”

Follow us on social media: