The Russian oil-export machine funding the Kremlin’s war in Ukraine is finally getting some grit in its gears.

Indian oil refiners — Moscow’s second-biggest customers after China since the 2022 invasion — will no longer accept tankers owned by state-run Sovcomflot PJSC because of the risk posed by sanctions.

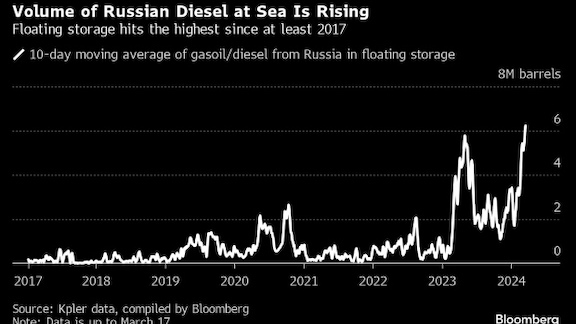

Since the start of October, the US has ratcheted up sanctions on the wider fleet of tankers moving Russian crude oil. Dozens of those targeted have been languishing ever since, and more barrels of Russian diesel are floating idly on the oceans than at any time since 2017, according to analytics firm Kpler.

Taken together, these moves have the potential to gradually constrict Russian petroleum revenues, a key policy goal of the US and its allies as they seek to thwart military aggression by President Vladimir Putin.

The Group of Seven’s approach to sanctions on Russia has been characterized by its refusal to cause any pain to its own economies in the form of higher oil prices. Washington came up with the so-called price cap policy precisely to soften the sanctions that were being cooked up in Brussels. And since the war started two years ago, Russia has continued to export huge amounts of oil.

While there’s no expectation of drastic supply cuts at this stage, the question is how far western regulators will go in tightening the screws while oil prices head towards $90 a barrel and President Joe Biden begins a grueling election campaign with painful inflation still in voters’ minds.

“It’s a growing squeeze on Russian export flows, particularly to India,” said Richard Bronze, head of geopolitics at consultant Energy Aspects Ltd. “We’re at the stage where sanctions-related friction is becoming very evident.”

Since October, the US has designated 40 individual Russian oil tankers. Four of the more recently targeted ones are continuing to make deliveries, but no sanctioned ship has collected a cargo since being named by the US Treasury, tanker tracking data compiled by Bloomberg show.

Now, an increasingly tough trading environment has delivered a powerful symbolic blow to the Kremlin as India — a stalwart commercial ally throughout war — shuns its fleet. At the same time, Ukraine has started blowing up Russian oil refineries, though it’s not clear how much support for the strategy it enjoys in Washington.

“We’re definitely seeing stepped up US sanctions pressure on both Russian crude and on exports,” said Greg Brew, an analyst at Eurasia Group in New York. “It comes at a time when the US is struggling to send more aid to Ukraine, when Ukraine’s fortunes on the battlefield are starting to decline, and when Russia appears to be gaining the upper hand.”

State-run Sovcomflot transported about a fifth of all Russia’s crude deliveries to India last year. The figure appeared to be in decline even before the news that nation’s refineries would no longer accept the ships.

“We expect and welcome that global oil buyers will be much less willing to deal with Sovcomflot than in the past,” a US Treasury spokesperson said, adding that the measures should have no oil market impact because Russia will maintain an incentive to sell oil.”

Now that fleet will need to find work elsewhere — and there are signs it’s struggling. At least seven of the vessels have come to a halt in the Black Sea and disappeared from digital monitoring systems, tanker tracking by Bloomberg shows. Sovcomflot admitted this week that sanctions had hurt its operations.

“The targeting of Sovcomflot represents a significant tightening of US sanctions against Russia,” said Janis Kluge, senior associate for Eastern Europe and Eurasia at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs in Berlin. “It will not solve the problem of circumvention, but it will drive up shipping costs and price discounts for Russian oil.”

Even so, Russia can still draw on a so-called “shadow fleet” of vessels amassed shortly after the 2022 invasion — often older ships without proper insurance and with unclear ownership — to make its deliveries. By some estimates, there are as many as 600 such carriers in operation, alongside Greek tankers that continue to serve the trade under the G-7 price cap.

Delivery costs for Russian oil are huge. It costs about $14.50 a barrel to delivery a Baltic Sea cargo to China, according to data from Argus Media. Well over half that sum is attributable to sanctions, it estimates.

“Whether this turns into actual supply losses will depend on how quickly workarounds are found for freight issues and whether Russian sellers are willing to deepen discounts,” said Bronze at Energy Aspects.

A further setback for Moscow has emerged in its sale of refined fuels. An average of 6.2 million barrels of Russian diesel was floating in the 10 days to March 17, according to data from Kpler That’s the highest the measure’s been since at least 2017.

While it’s not clear that sanctions have caused the buildup, it’s striking that so much product is accumulating at a time when drone strikes ought to have curbed supplies.

“Washington still has powerful tools to hurt Russian oil exports, but has used them cautiously, fearing a spike in gas prices in an election year,” said Kluge.

Follow us on social media: