The unprecedented shutdown of one of the largest U.S. pipelines after it was crippled by a cyberattack has triggered warnings of major disruption to fuel supplies and concern that its restart will be neither quick nor straightforward.

Colonial Pipeline turned off key systems late Friday after an attack involving ransomware, and was still down late Sunday. There are few precise details about what happened at Colonial, which says it normally transports about 45% of all the fuel consumed on the East Coast and in the Northeast. It says it’s working to return to normal. Various branches of the U.S. government are monitoring the situation.

The U.S. oil and gas industry is used to dealing with outages, like those caused by hurricanes or other extreme weather—see February’s winter storm in Texas. Energy companies practice for those scenarios and pride themselves on quickly restoring service.

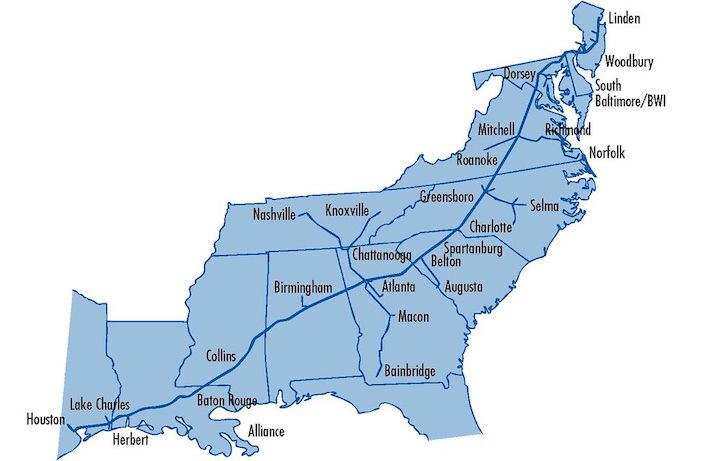

What makes the current situation alarming is that it’s rare for such a vital and large piece of infrastructure—Colonial stretches all the way from Texas to New Jersey—to be knocked completely offline. The outage is the biggest single disruption to physical energy supplies since Saudi Arabian oil operations were attacked by drones in 2019, according to Bob McNally, a former senior White House policy adviser.

“Restarting the pipeline is easy if no actual damage was done to it,” said McNally, who now runs Rapidan Energy Group, a consulting firm in Washington. “The question is whether the attack was limited and contained and it didn’t cause any physical damage to it.”

Cyberattacks such as the one faced by Colonial would typically trigger an emergency response plan. Those usually involve a war room setup where executives are provided with real-time updates by the cybersecurity and operational teams, as well as the company’s general counsel.

Pumping different refined products along the entire length of Colonial safely and efficiently requires sophisticated, automated systems. Operating without all of them functioning is extremely challenging, according to Niyo Pearson, an oil and gas adviser for Cynalytica, a cybersecurity firm. He pointed in particular to Colonial’s technology regulating the pressure of gas used to push liquids through the pipe.

That “is the brains of the system,” Pearson said. “It controls the settings on the pipeline, what the pressure is, remote operation of valves,”

Trying to restart the flow of gasoline without that capability would require Colonial to send people to various facilities along the length of the pipeline, and the expertise needed to operate under those conditions is limited, he said.

“If they can restore their systems in 72 hours—or even a week—they’ll be in good shape,” Pearson said. “It gets really tough after that.”

In the meantime, fuel producers including Marathon Petroleum Corp. are weighing alternatives for how to ship their products to the Northeast in case Colonial isn’t restored quickly. Traders and fuel shippers are seeking barges and other vessels to deliver gasoline that would have otherwise been shipped on the pipeline, according to people familiar with the matter. Others are securing tankers to temporarily store gasoline in the U.S. Gulf in the event of a prolonged shutdown, the people said.

Inventories offer minimal cover, ClearView Energy Partners said in a research note. Tankers leaving Rotterdam could take up to 14 days to make the trip to the New York Harbor. The Midwest could theoretically send some of its supplies to the East Coast via rail and barge, but the region’s inventories are tighter than in previous years, ClearView said.

“The Colonial outage comes at a critical juncture for the recovering U.S. economy: the start of the summer driving season,” ClearView said. “We therefore think lawmakers could begin a ‘blame game’ immediately, and a sustained disruption that leads to a significant pump price spike could increase prospects of domestic policy interventions.”

Follow us on social media: