Palm oil storage tanks in Indonesia, the world’s biggest producer of the commodity, may start brimming as producers hold stocks to comply with the government’s move to ban exports of cooking oil and its raw materials to cool domestic prices.

In less than one month, stockpiles will climb further than five million tons and companies may start to slow down operations because they would not know where to store their output, Secretary General of the Indonesian Palm Oil Association Eddy Martono said in a phone interview on Monday.

“That means companies could stop buying palm’s fresh fruit bunches from farmers,” said Martono. The ban, which is set to take effect Thursday, awaits more detailed rules from relevant ministries or it will put industry members in a difficult situation without any clarity on which products are affected exactly, he said.

The government will only halt exports of bulk and packaged refined, bleached and deodorized palm olein, according to people familiar with the matter. The ban excludes shipment of crude palm oil and RBD palm oil.

The ban may only benefit Malaysia, the world’s second largest producer of the most consumed cooking oil, he said. Local prices of palm oil may only decline temporarily before they start to increase again in response to ensuing higher edible oil futures, said Martono. Palm oil futures in Kuala Lumpur rose as much as 7% on Monday to 6,799 ringgit a ton.

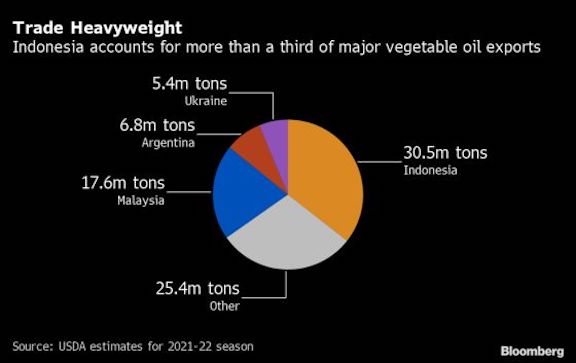

Indonesia produces more than 50 million tons of palm oil a year and exports about 60% of its output in the form of processed palm oil, including cooking oil and biodiesel. The government has been taking measures to cool prices of cooking oil since January, ranging from capping retail prices to imposing a domestic market sale, increasing exports levy and providing subsidy to consumers, without much success.

Prices of bulk and unbranded cooking oil remain persistently above the government’s target price of 14,000 rupiah a liter, while those of premium package goods have risen 19% in April from January, according to trade ministry’s data.

Rapeseed Crush

India, a top buyer, has sufficient supply of edible oils to cover for three to four weeks of demand, according to Sandeep Bajoria, chief executive officer of Mumbai-based Sunvin Group. “Also, we have ample stocks of rapeseed right now so we will crush more of rapeseed to boost our supplies. That will help us tide over this difficulty,” he said.

He estimated the ban to last no more than three of four weeks as local prices should cool down with the end of the Eid festival season and as the country has limited capacity to store freshly produced oil.

Palm oil imports by India may fall to about 400,000 tons in May because of the Indonesian ban, from an estimated 575,000 tons in April, Bajoria said, adding that the country could also fill the gap by using existing stocks of other edible oils.

Still, he thinks the Indian government should negotiate a deal with the Indonesian government as a long-term trading partner. “Disruption like this is not a healthy way to keep a good relationship between a seller and buyer,” he said.

Indonesia should also brace for a potential tit-for-tat trade retaliation move, as crude palm oil is exported mostly to China, India, Pakistan and the U.S., which the nation relies on for manufactured goods imports, said Satria Sambijantoro, an analyst at PT Bahana Sekuritas in a report on Monday.

Follow us on social media: