Russia’s grip on global food supply is tightening after two of the biggest international traders said they would halt grain purchases for export from the country.

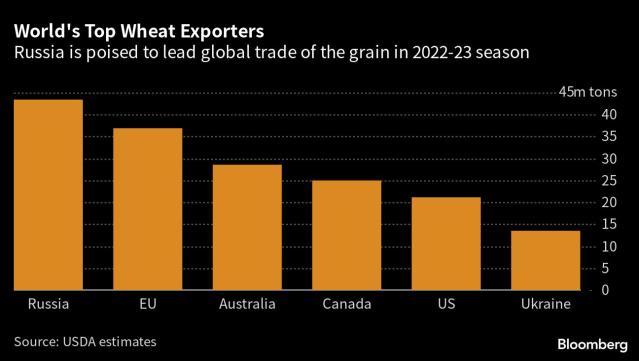

The exit of Cargill Inc. and Viterra means Russia, the world’s largest wheat exporter, will have more control over its food shipments and reap more of the revenues. Russia’s dominance in the global grain market was laid bare by the war in Ukraine, with prices surging last year amid supply disruptions.

Archer-Daniels-Midland Co. is also weighing options to quit its main Russian operations, according to people familiar with the matter. Louis Dreyfus is considering reducing its presence in the country, the Kommersant newspaper reported.

For Russia, “we can assume that it will be easier to control the export flows if authorities want to do that, as it’s easier to deal with local players,” said Andrey Sizov, managing director of researcher SovEcon.

1. Why are companies like Cargill and Viterra leaving Russia?

Cargill and Viterra have been under pressure to give up their assets in Russia since at least December, when a series of influential figures — including governors of the country’s major grain producing regions — called on Moscow to limit foreigners’ influence in Russia’s food market.

Government-funded traders had already been grabbing a bigger chunk of the market as President Vladimir Putin made food sovereignty a policy priority and as grain exports became a symbol of geopolitical power. State-backed bank VTB gobbled up market share in recent years from Viterra and Cargill. State-backed OZK, also known as United Grain Co., is also among the top five shippers.

It’s likely that the multinationals were encouraged to make a decision ahead of the new wheat export season, Sizov said, as exporters will start to sell the new crop in May. Meanwhile, Russia has been making it increasingly difficult for foreign traders to obtain the paperwork necessary to export their grain, according to people familiar with the matter.

The international trading companies have benefited from Russia becoming a major global grain exporter over the two to three decades they have been operating there. During that time, Russia’s wheat exports boomed fivefold, making the country’s wheat the global benchmark price for trade.

2. Why does it matter for global food supply?

The departure of Cargill and Viterra leaves Russian grain supplies largely in the hands of domestic and government-funded companies, meaning Russia will control more of the much-needed revenue as war decimates its budget.

This means it could be easier for Russia to use food exports as a tool of geopolitical influence. Among the main buyers of Russian grain are countries in the Middle East and Africa that have avoided strong criticism of the invasion of Ukraine.

“If the Russian government gets more involved, it brings more risk from a market perspective,” said Matt Ammermann, a commodity risk manager at StoneX. “Until Russia proves itself, it’s a questionable supplier, even though everything is going to be moving forward as normal.”

3. What does this mean for grain prices and trade flows?

Russia’s agriculture ministry says the changes won’t impact the country’s export levels, but traders are watching for any signs of how Russia may try to influence prices or terms of trading. More government-to-government deals are likely to happen.

State-backed company OZK has already signed several wheat contracts with Turkish partners and said last year it wanted to “completely get rid of involvement of international traders and work directly with importing countries.”

The redrawing of the Russian grain market also makes it harder to track how grain from occupied Ukraine is being mixed in with Russian crops and shipped to world markets.

4. How will Russia’s grain get exported now?

Viterra and Cargill shipped around 14% of Russia’s grain volumes last season, so a big chunk of exports will continue as before. Viterra’s local team has set up a new business and will continue its work, according to Russia’s grain union. Cargill said that it will stop exporting grain sourced by the company in Russia from July, but will continue to buy cargoes from other firms.

Still, many insurers and shipping companies may be more wary of working with Russian firms due to sanctions-related risks. Food is not sanctioned, but some state banks involved in the grains business are. Russian state company Rosagroleasing is aiming to build more than 60 of the largest bulk ships for grain export, but that will take years.

5. What comes next?

Russian farmers will likely be the biggest losers as international traders exit. Fewer players reduces competition for their grain, said Dan Basse, the founder of consultant AgResource.

It’s unclear whether the country’s export prices will continue to serve as the global benchmark of the wheat trade.

“If it’s more state-controlled, we have diminished confidence in those offers and less transparency,” Basse said. “The world grain industry is kind of a loser here.”

Follow us on social media: