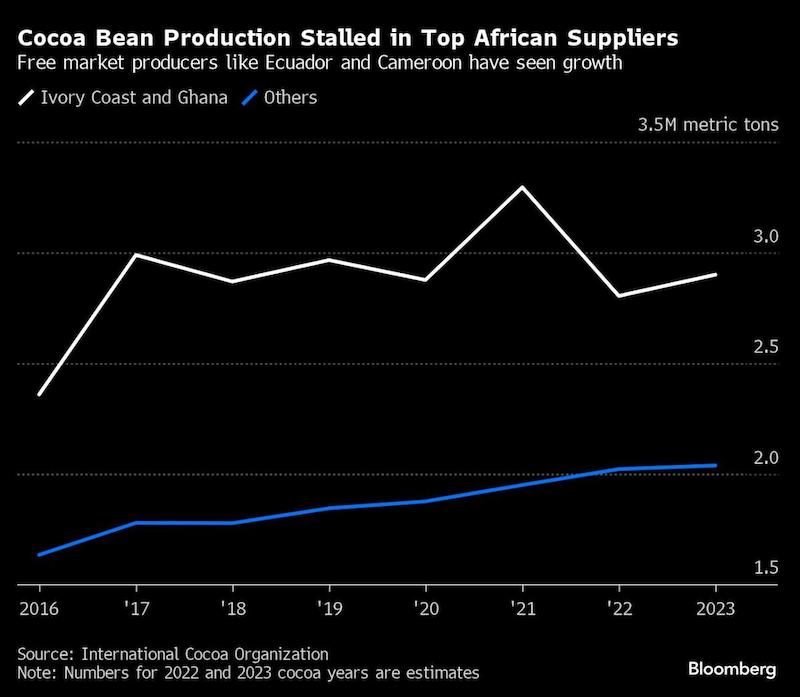

A rally that sent cocoa prices to a 46-year high should normally benefit the world’s largest producers. Instead, smaller growers are the ones reaping the rewards.

Prices in Ivory Coast and Ghana, which account for about 60% of global supplies, are set by governments based on sales made a year earlier. That means farmers are getting less money than counterparts in countries like Brazil, Ecuador, Nigeria and Cameroon, where growers profit almost immediately and can make ambitious plans to scale up production.

“On paper, if you are Ivory Coast and Ghana, rising prices should result in a response down the road, but the farmer price was set too low,” said Jonathan Parkman, the head of agricultural sales at Marex Group. “It’s the countries where markets are liberalized, like Ecuador and Brazil, that will benefit first.”

Ecuador has plans to expand production to match or even overtake Ghana by 2030, while Brazil is aiming to start exporting again by the end of the decade, according to grower and industry groups. Nigeria and Cameroon are also planning to raise output.

All of that is leaving Ivory Coast and Ghana behind, with some traders expecting production in the top growers will only start increasing in the season that starts in October. That’s when higher prices from forward sales will likely be passed on to farmers.

Cocoa futures traded in New York surged more than 60% last year, the biggest increase since 2001. Prices touched a 46-year high of $4,478 a metric ton on Wednesday.

The Ghanaian government, however, is only paying growers a fraction of that, at just under $1,800 a ton. In Ivory Coast, the price paid for the bigger of two harvests is around $1,600. As a result, production in the two nations will take longer to recover.

In Ecuador, where the market is liberalized, output is expected to reach 800,000 metric tons by 2030, according to Ivan Ontaneda, president of the country’s National Cocoa Exporters Association, or Anecacao. That would put the country’s output near or above that of Ghana, the second-largest producer.

“We don’t have internally controlled prices,” Ontaneda said in a November interview. “If the market is going up, we pay 90% of the $4,000 that goes for cocoa right now. That’s very, very important for the producer.”

Brazil, meanwhile, is looking to double its production by the end of the decade and restart exports, according to the country’s cocoa commission, Ceplac. Farmers are expanding into new areas in a shift for the country that was once a prominent global supplier but had its crops ravaged by a tree-killing disease back in the 1980s.

Cameroon aims to raise its output to 600,000 tons before 2030, up from the current production of over 295,000 tons, according to Gabriel Mbairobe, Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development. Higher prices lured new farmers like John Fondzenyuy, who used to work in construction before starting a new farm in the producing area in Makenene.

“Construction material has become expensive and many people are no longer building,” said Fondzenyuy, who expects to harvest his first pods from 2025. “I think cocoa will give me more money.”

Ondo, a state in southwestern Nigeria, is targeting an 88% boost in production to 150,000 metric tons by 2025, said Segun Awolumate, the chairman of Ondo’s Cocoa Development Council. Efforts from his council, the government and farmers have focused on rehabilitating existing farms to nearly double crop yields.

Growers in Abia in the southeastern part of the country are returning to abandoned farms, said John Kalu, the chairman of the state’s arm of Cocoa Farmers Association of Nigeria.

“Every cocoa farmer in the state wants to double, even triple, last year’s production in the current year,” Kalu said. The state is looking to reach 200,000 tons by 2029.

To be sure, increases in production will be limited by European Union regulations. New legislation going into effect at the end of the year prevents products linked to deforestation from being sold in the bloc, the world’s largest cocoa and chocolate consuming region.

Even with more output from smaller producing countries, the world is still heavily reliant on Ivory Coast and Ghana. And any newly-planted seedlings take at least three years to pay off.

Ivory Coast and Ghana are also facing structural barriers to production including swollen-shoot virus and an aging tree stock that could continue to affect crops even if weather conditions improve, said Steve Wateridge, the head of research at Tropical Research Services.

If those two producers “are both in long-term decline, then Ecuador, Nigeria, Cameroon, Brazil, Peru — they’re not going to be able to make up the slack anytime soon,” he said.

Follow us on social media: