Among the marvels of American industry on display at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893 were the original Ferris Wheel and the world’s first zipper. But for many of the exhibition’s tens of millions of visitors, it was the 200 cloth and fabric manufacturers, including more than 60 cotton-specific ones, that really stoked their nationalism.

“The American man or woman who does not feel pride” in the growth and prowess of the US textile industry “must be singularly wanting in patriotism,” read the post-fair edition of the Davison’s Textile Blue Book, an annual directory for the industry. “No one needs to be told that in these textile industries there is promise of a great future.”

No more. Once so key to the plantation economy of the Deep South that politicians sometimes referred to their diplomatic strategy simply as “King Cotton,” the crop’s demand from US manufacturers is on an unrelenting — and accelerating — decline. There were nearly 900 US cotton mills operating around the time of the Chicago expo. That number is today around 100, the National Cotton Council estimates, after eight closed in the last five months of 2023 alone.

With domestic textile manufacturing nearly gone, cotton farmers who are this month starting to sow millions of acres from California to the Carolinas are less likely than ever to find a buyer for their next harvest at home.

In other sectors, a recent push for re-shoring has brought a new wave of manufacturing back to the US, especially when it can help relieve shipping snags and geopolitical tensions — think semiconductors or industrial metals important for developing a domestic electric-vehicle supply chain. But textiles aren’t seen as having “the same criticalness as a chip or certain minerals,” said Erin McLaughlin, a senior economist at the Conference Board, a nonprofit think tank — even if the urgent need for protective equipment like masks during the pandemic highlighted the importance of a US industry.

The numbers are stark. This year, US textile mills are expected to process the least cotton in 139 years. Textile factory employment in 2023 fell to its weakest annual rate in records going back more than three decades, Bureau of Labor Statistics data show. American farmers continue to plant the fibrous shrub for overseas buyers, but even that market has its challenges: US cotton exports are on track to fall for a third straight year, putting No. 2 exporter Brazil within striking distance of the top spot.

Decades of competition from cheaper overseas production and the adoption of synthetic materials are behind the textile industry’s domestic decline, with more recent changes in US government policy speeding its demise. In 2016, Congress amended the 1930 Tariff Act to allow importers to ship in customers’ orders valued below $800 duty-free. Raising the so-called de minimis exemption, along with the Covid-era boom in e-commerce, has allowed foreign fast-fashion companies like Shein to make major inroads. Elevated inventory backlogs and high inflation further dampened the country’s factory demand for its own cotton crop.

“Our industry and my company have never seen the level of economic difficulty that we are currently facing,” Andy Warlick, chief executive officer of North Carolina-based yarn manufacturer Parkdale Mills, said in testimony to Congress stressing the need to close the de minimis loophole. “Nearly every textile facility in the country is now running at significantly reduced capacity, and many production lines are completely idle.”

One of those factories is 1888 Mills LLC’s plant in Griffin, Georgia, which has manufactured terrycloth items like towels since it bought the more than century-old mill in 1996. The company announced in January that it would be closing the mill — its sole factory in the US — and laying off 180 workers in April. It operates mills in lower-cost Pakistan and Bangladesh, which will remain open.

The company had already invested in new equipment, automation and more employee training to make the mill more competitive, but “in the end, it wasn’t enough to really move the needle for us,” said Lexi Schladenhauffen, 1888 Mills’ chief experience officer. The closure “is a disappointment and a sadness.”

There have been a few short reprieves when the nation’s cotton industry seemed to be on the upswing. Mill use made a brief recovery in the 1990s, when programs like the Caribbean Basin Initiative and the North American Free Trade Agreement encouraged the US to export cotton yarn and fabric to be turned into clothes in other countries, before being sent back to be sold, according to the US Department of Agriculture. But that production sank again once the World Trade Organization began phasing out quotas on textile and apparel imports in 1995, enabling countries like China to export more to the US.

More recently, demand edged higher in 2021 as consumers flush with government stimulus checks after pandemic lockdowns went shopping. But the boost didn’t last: Companies stocked up on product to meet elevated consumer demand just as people were shifting their spending back toward travel and entertainment, said Brian Yarbrough, a senior analyst at Edward Jones.

To be sure, domestic cotton demand will never completely go away. In addition to a subsect of consumers who seek out American-made or even hyper-local goods, the Department of Defense requires the purchase of some US-made textile and apparel items from clothing to tents. Pockets of the textile industry have also found new industrial uses. At North Carolina State University’s Wilson College of Textiles, faculty and students work on products like heat and chemical-resistant fabrics. The college is even home to a dedicated institute working on nonwoven fabrics, which are often used in industries like medical, automotive and construction.

There have been “substantial changes” and a shrinkage in “certain areas of the textile supply chains substantially, but it’s wrong to say it’s gone,” said David Hinks, the college’s dean. “What’s happening at the moment is a tremendous investment in reinvigorating the industry to be more competitive and more sustainable.”

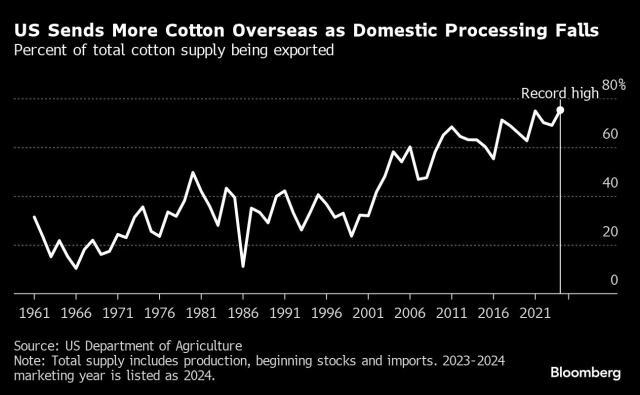

US farmers are also able to rely on a vibrant export market — for now. More than three-fourths of US cotton supply this year will be exported, government data show, the highest share on record. That outsized reliance on export demand leaves farmers more susceptible to geopolitics and other disruptions, said Gary Adams, CEO of the National Cotton Council. The US cotton textile industry “was always a stable and secure demand source. You weren’t subjected to the same issues of market volatility,” he said.

The sector, mostly located in the north of the US until the late 1800s, moved south after the Civil War. That gave companies better proximity to the cotton crop, often harvested by formerly enslaved people now working as poorly paid sharecroppers. Companies often settled in places with “good enough roads to get the products in and out, but were sufficiently isolated so as not to encourage unionization,” said Peter Coclanis, an economic historian and professor at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Although in some cases, losing manufacturing jobs to overseas has ushered in a new age of high-income service jobs, many former textile towns, distanced from interstate highways or larger cities, are still struggling to bring in new employers or developers.

“Many parts of the rural South are in real crisis today,” Coclanis said. As global competition hurt American textile manufacturing, “these places lost a terribly high number of jobs and basically the whole community has collapsed.”

As one-time cotton mills have been abandoned or demolished across the South, policies are emerging to encourage residents to redevelop or preserve them as historical properties. Some have found new lives as apartments, retail spaces and wedding venues.

For decades, the namesake mill of Mount Holly, North Carolina, sat empty. Now, Robbie Delaney is pouring nearly $4 million into renovating the county’s oldest remaining cotton mill into a rum distillery and event venue, which is slated to open in June. When guests enter the new home of the Muddy River Distillery, they’ll be greeted by an antique circular knitting machine original to the site. A host will invite kids to spin the gears that more than a century ago helped loop yarns into fabric.

“This mill named the town,” Delaney said. “It sat empty for years and now it’s got new life.”

Follow us on social media: