U.S. agricultural exports fall victim to drought and low river levels. The conundrum of the ag transportation is the barges on the Mississippi River move north-to-south while rail routes run east-to-west.

As if North American supply chains needed another challenge, a drought that began in the summer of 2020 has compromised freight barge traffic on the Mississippi River. Record-low October water levels on the river at Memphis measured nearly 11 feet lower than the previous record set in 1988.

To accommodate a shallower draft, operators must reduce loads on each barge and the number of barges that are lashed together in a “tow.” A typical barge can accommodate 50,000 bushels of soybeans, and a 15-barge tow can carry 750,000 bushels. Each foot of reduced water depth requires as much as 6,700 fewer bushels of soybeans being loaded per barge, or over 100,000 bushels per tow. With barges accommodating lower volumes, the capacity of the river system as a whole becomes limited, and that increases the costs of transportation.

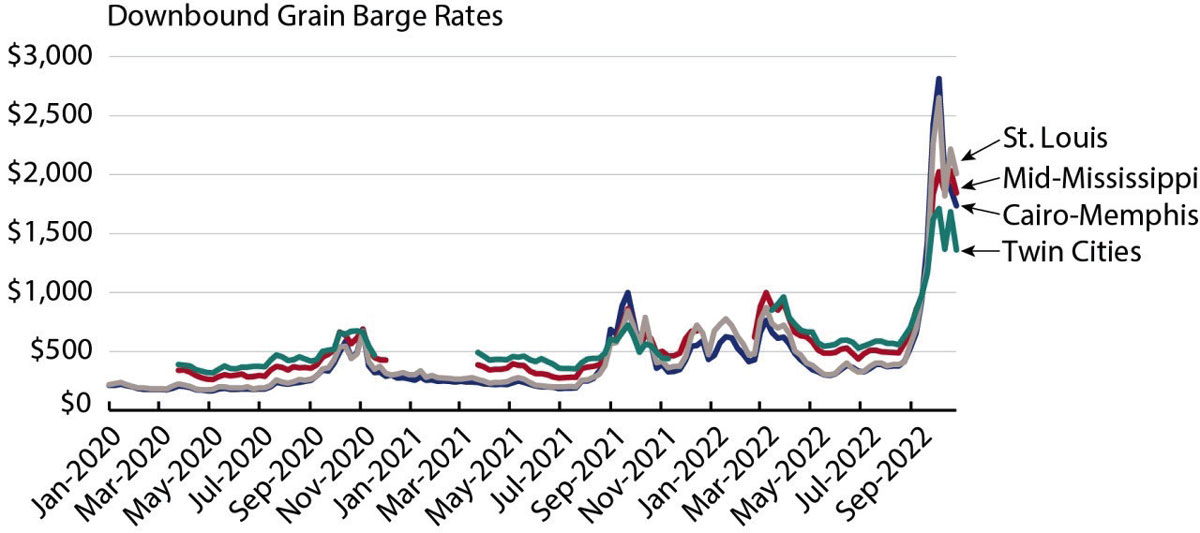

According to a report released by the Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, barge rates on the river have historically moved in the $20 per ton range. But in mid-October of this year, barge spot rates in St. Louis hit $106 per ton before falling to $88 per ton later in the month. Forward rates were also elevated, although not to the same extent. One-month contracts in St. Louis fetched $59 per ton in November, while a three-month contract cost $34 per ton.

Impact on Soybean Exports

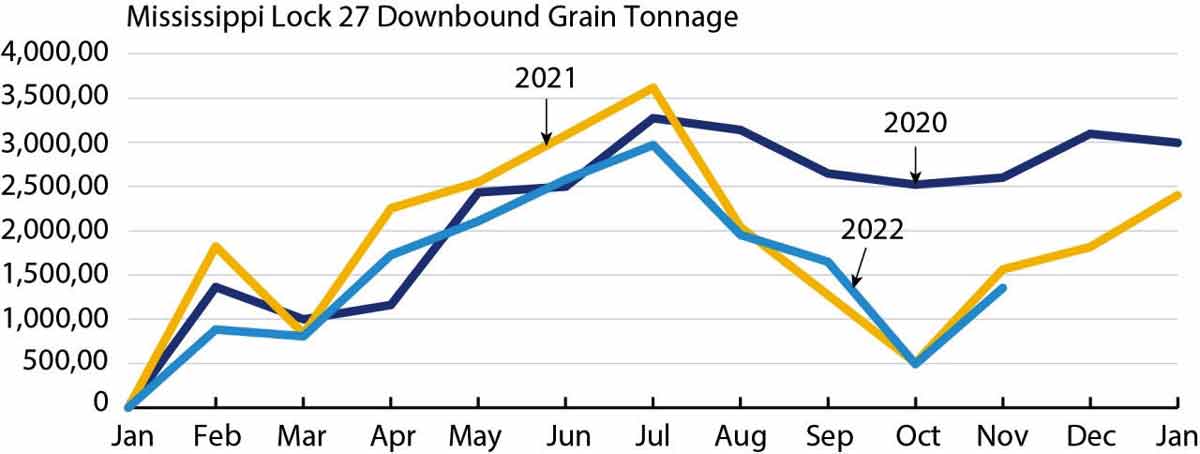

“The record low Mississippi River has led to a severe disruption in the barge transportation system vital for the shipment of grains and farm inputs,” said the report. “We continue to observe an extreme divergence between the Gulf and regions along the river,” leading to elevated price premiums along the Gulf and deteriorating prices inland. The number of grain barges unloaded in New Orleans this year through October was down by as much as 30% compared to recent years.

These barge disruptions come at a particularly bad time for U.S. soybeans. Three-fifths of all soybean exports occur between October and January, and 94% of U.S. soybean exports rely on Mississippi River barges to get to Louisiana ports for export. “Soybean exports were particularly slow in the month of September,” said the report. “Exports picked up in October but were still generally down relative to the three-year average,” a phenomenon not seen since the tariff wars of 2018, when China imposed retaliatory tariffs of 25% on U.S. soybeans, leading to a collapse in export demand.

The slowdown in soybean exports is contributing to depressed U.S. agricultural export volumes generally, according to projections from the United States Department of Agriculture. U.S. agricultural exports for the fiscal year beginning in October 2022 were projected to be $190.0 billion in November, down $3.5 billion from the department’s August forecast. “This decrease is primarily driven by reductions in soybeans, cotton, and corn exports,” said a USDA report.

Projected fiscal year 2023 U.S. oilseeds exports were down $2.3 billion from August to $44.3 billion in November and down $1.4 billion from the previous year. “Values are down almost entirely on a $2.4-billion reduction in soybeans,” said the USDA report. Projected agricultural imports, meanwhile, were increased by $2 billion from August, thanks to a strong dollar, which also provides “a headwind to the export forecast.”

Transportation Conundrum

Rail transportation, which could potentially carry large volumes of agricultural commodities, doesn’t present much of an alternative for shippers along the Mississippi, because “options down the Gulf, are constrained,” noted the University of Illinois report, “and come at a higher cost.” In addition, explained Peter Friedmann, executive director of the Agriculture Transportation Coalition (AgTC), “the barges and our river system go north to south, and most of our railroads go east and west, so there is not a simple replacement of rail for barge.” That point was driven home by the Illinois report, which noted that soybean prices are “holding up better in the Dakotas, which has better access to the Pacific Northwest export routes.” Inland areas of Kansas and Nebraska and Eastern production areas of the United States are also “faring better” because they “do not rely upon the Mississippi River.”

Nor do trucks provide a realistic alternative for delivering soybeans to seaports. “One barge holds the equivalent cargo of 138 trucks,” said Friedmann. “There are thousands of barges sitting on the bottom of the river, not moving. We do not have hundreds of thousands of extra trucks sitting around nor hundreds of thousands of extra truck drivers sitting around, able to carry that cargo.”

The Mississippi River situation contributes yet another component to the global inflation in food commodity prices. “General inflation has been running 7% to 9% in recent months,” noted Roger Cryan, chief economist at the American Farm Bureau Federation, “while the most recent Consumer Price Index report for food consumed at home reveals a 12% increase over the past year.

“Other contributing factors to increased [food] costs include supply chain disruptions and the war in Ukraine,” Cryan added.

In most cases, according to Friedmann, buyers of U.S. agricultural exports are hard pressed to find alternative sources that can supply volumes at the scale of U.S. producers. “So, the pricing goes up,” he said. “The delivery cost is skyrocketing because you can’t get the product down the river,” and alternative transportation modes and port routings are not available in many cases.

All of which raises the question of when the situation on the Mississippi River will normalize. Friedmann’s short answer: The barges are “going to sit there until we get some rain.”

“It is not clear when this might occur,” said the Illinois report, “but we do think it is helpful to be mindful of the seasonality of the river’s stages.”

The worst-case scenario, according to the Illinois report, is that the river will be navigable by March 2023. “However,” the report added, “this may provide little comfort to farmers, particularly soybean producers, as Spring will be the time Brazil starts ramping up its soybean exports. Further, even when the rivers rise, the backlog in shipping may take some time to unwind.”

Follow us on social media: