Agriculture shippers complain proposed FMC reg allows carriers too much leeway.

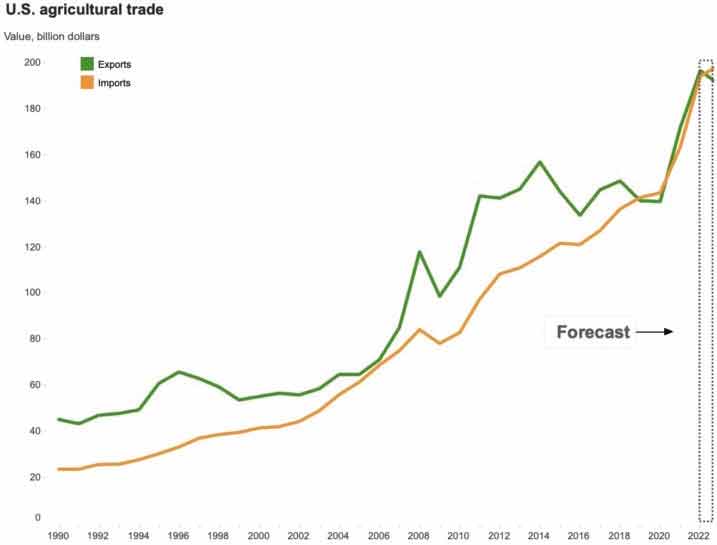

Over the last three years, U.S. agricultural exporters have complained that their cargo wasn’t being loaded at seaports, as ocean carriers prioritized the repositioning of empty containers to Asia to accommodate a surge in high-paying imports. Federal Maritime Commission (FMC) documents show that the average rate of a 20-foot dry container moving from Shanghai to the U.S. West Coast reached $8,130 in January 2022, while the rate for the backhaul was $1,220. The import/export ratio in the Asia-to-U.S. trade dropped from 39% in 2019 to 29% in 2021, a pattern that continued into 2022. As a result, according to the Agriculture Transportation Coalition (AgTC), 22% of U.S. agricultural exports in 2021 were not delivered.

OSRA 22 and Ag Shippers

The Ocean Shipping Reform Act of 2022 (OSRA 22), which was signed into law on June 16, was meant to remedy this situation on behalf of agricultural exporters. OSRA 22 prohibited vessel-operating ocean carriers from discriminating against U.S. exporters and “unreasonably” refusing cargo space accommodations. The bill required the FMC to write the rules that would define unreasonableness.

In September, the FMC issued those draft regulations, eliciting howls of protests from agricultural exporters, and a far different reaction, although not an overly enthusiastic one, from ocean carriers. Under the new proposed rulemaking (NPRM), an “unreasonable” refusal to deal or negotiate with respect to vessel space is to be dealt with on a case-by-case basis. Among the factors to be considered include whether the carrier had a documented export strategy designed to promote the efficiency of cargo movement; whether the carrier engaged in good faith negotiations and made fair and consistent business decisions; and whether “legitimate transportation factors” in the refusal came into play, such as the character of the cargo, schedules, and the adequacy of facilities. Neither “the status of the shipper” nor “commercial convenience alone,” the NPRM said, is to be considered “a reasonable basis for a common carrier’s refusal to deal or negotiate.”

An ocean common carrier’s categorical exclusion of U.S. exports from its backhaul trips would create a rebuttable presumption of unreasonableness under the NPRM. To overcome the presumption, carriers may provide a certification by a U.S.-based compliance officer that explains the ocean common carrier’s decision and specific criteria used to reach a decision and/or evidence of good-faith consideration of a proposal or request to negotiate.

As agricultural exporters see it, the rulemaking allows a carrier’s business development strategy to be used as a reasonable basis to refrain from carrying export cargo. “The NPRM provides carriers a loophole large enough to sail a 22,000 TEU ship through—with room to spare,” wrote the AgTC in comments filed in response to the NPRM. “It suggests a greater interest in promoting ocean carriers’ profitability than in supporting the growth and development of U.S. exporters.”

Ocean Carriers vs Ag Shippers

The FMC’s brief under OSRA 22 includes “promot[ing] the growth and development of United States exports…” The AgTC wants the FMC to scrap the proposed rule and start from scratch.

Carriers contend that it is their practice to refuse service to individual shippers “only when that shipper has presented a circumstance in which the carrier feels a business transaction cannot reasonably be undertaken,” the World Shipping Council (WSC) asserted in its comment.

The WSC also objected to the NPRM’s view of a “carrier granting special treatment to…a regular customer” as “likely…unreasonable.” The Shipping Act, the WSC contended, allows shippers and carriers to structure relationships according to their needs in individual service contracts.

OSRA 22 did not limit the Shipping Act’s authorization to enter into confidential contracts, the group stated, so “there is no legal basis” for the language proposed by the FMC. “The same principles of freedom to contract continue to apply,” the WSC concluded, “and the commission must make clear in any final rule that this is the case.”

Dole Ocean Cargo Express, an ocean carrier, demanded that language in the rule be removed requiring a carrier’s business decisions with respect to service contracts to be applied fairly and consistently. “It is the essence of service contracting,” said the company’s comment, “that carriers be able to treat each customer differently.”

The NPRM has also ignited the ire of OSRA 22’s sponsors in the U.S. House of Representatives, including Representatives John Garamendi (D-CA) and Dusty Johnson (R-S.D.). In November, they wrote a letter to FMC chair Daniel Maffei asking the commission “to uphold congressional intent.” Garamendi and Johnson object to the FMC’s definition of “unreasonable” as applied to vessel space accommodation and asserted that the NPRM provision will not protect American shippers and exporters from unfair business practices of foreign ocean carriers.

“The FMC’s current definition of ‘unreasonable’ refusal is so feckless it has us wondering, What was the point of passing OSRA in the first place?” the letter said. “We all witnessed the havoc foreign-flagged ocean carriers wreaked on our ports in 2021, price gouging shippers and leaving American exporters high and dry. If this definition stands, they could easily do it again.

Congressional Intent

“This proposed definition is not in line with congressional intent,” the letter continued. “It needs to be remedied for the sake of our farmers, exporters, and manufacturers who already faced extreme losses at the hands of foreign carriers.”

But the problem with the representatives’ protest of the FMC’s failure “to uphold congressional intent” is that Congress itself failed to guide the FMC on how to determine what qualifies as unreasonable behavior in the legislation it passed. As the NPRM noted, “key terms and phrases,” including “’unreasonably,’ ‘refuse to deal or negotiate,’ and ‘vessel space accommodations, are not defined” in OSRA 22.

When he introduced the initial version of the bill in August 2021, Garamendi said that Congress would defer to the regulators to set the definitions of key legislative provisions. So, when Garamendi asks, “What was the point of passing OSRA?” if the NPRM fails to uphold congressional intent or adequately protect agricultural exporters, the question is perhaps better directed to himself and his congressional colleagues, rather than to the Federal Maritime Commission.

Follow us on social media: