September groundbreaking marked shift from project planning to construction

The New Jersey Wind Port is no longer merely on the drawing boards. Activity related to its construction has begun in earnest. On September 9, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy and U.S. Department of Labor Secretary Marty Walsh ceremonially broke ground on the Salem County facility, which is slated as a marshaling port for the U.S. offshore wind industry.

The New Jersey Economic Development Agency (NJEDA) says that the state’s $300 million investment in the wind port will create thousands of assembly, operations, and construction jobs. The port will provide a location for staging and assembly, and eventually also manufacturing, activities related to offshore wind projects, 17 of which are planned off the East Coast of the United States from Massachusetts to Virginia.

That is one reason the Salem County site was chosen, noted Tim Sullivan, NJEDA’s chief executive officer, adding that it has “easy access to more than 50% of the available East Coast offshore wind lease areas.”

NJ Wind Port Construction to Start in December

The New Jersey Wind Port is being developed on an artificial island on the eastern shores of the Delaware River, southwest of the City of Salem. Preconstruction activities such as concrete removal are now ongoing, while major construction on the port is due to start in December 2021 and operations are scheduled to begin in late 2023 or early 2024. In July, NJEDA formally chose AECOM Tishman as the construction manager for the site, and in recent days took other steps to ensure the project’s forward progress, including signing the ground lease with the site’s owner, the power company Public Service Enterprise Group (PSEG), on September 14. (See New Jersey prepares for its wind port)

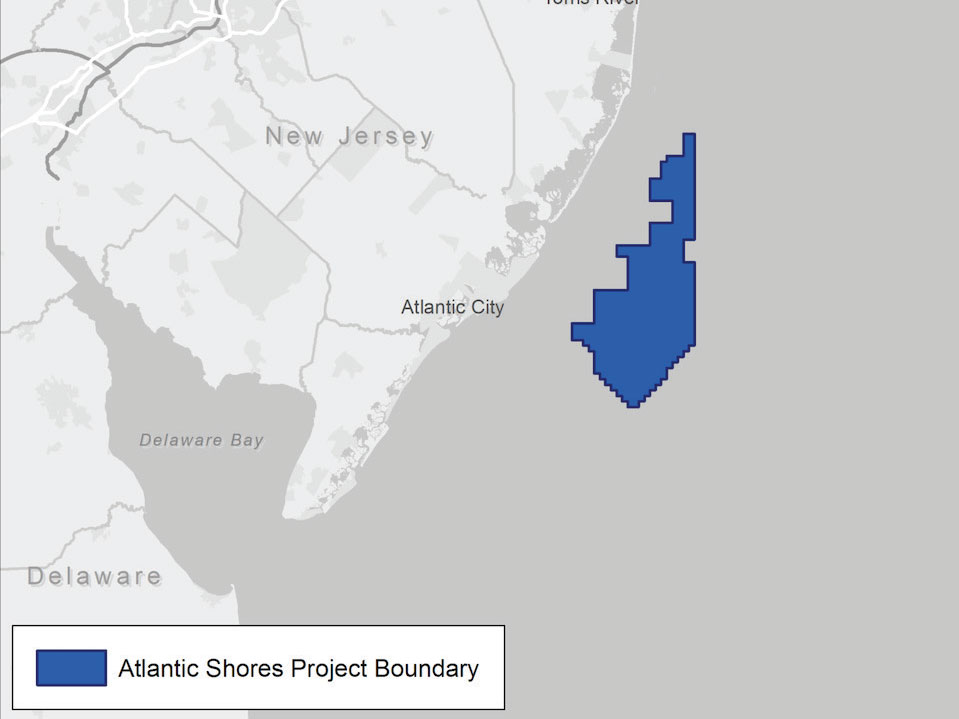

In June, the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities (NJBPU) made what it claims is the nation’s largest award of offshore wind capacity to date—a total of 2,658 megawatts to Atlantic Shores Offshore Wind, a project of Shell New Energies and EDF Renewables North America, and Ocean Wind II, a joint venture of the Denmark-based wind company Ørsted and PSEG. The award brings New Jersey’s total planned offshore wind capacity to over 3,700 megawatts, around half the 7,500 megawatts of offshore wind energy the state wants to bring online by 2035.

The remainder of the 7,500 megawatts of offshore wind energy is currently being competitively bid by PJM Interconnection, a regional grid operator, and NJBPU, seeking upgrade options to the existing grid to facilitate offshore wind energy inputs. The solicitation window closed on August 13, and NJBPU and PJM are now evaluating submissions. “New Jersey is the first and only state to utilize this approach,” said Joseph Fiordaliso, president of NJBPU.

Offshore wind projects slated for development along the East Coast are expected to require over $150 billion of capital investment by 2035, and the U.S. offshore wind industry is projected to create over 83,000 jobs, mostly along in the Northeast. International precedents have shown that wind port developments spur economic activity, one reason why New Jersey and other locations are jumping on the bandwagon.

The ripple effects of the state’s investment in the wind port are already being seen in New Jersey. Among other recent developments, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) granted the South Jersey Ports Corporation $9 million to expand barge capacity and intermodal rail connectivity at the Port of Salem. The project represents an “example of the broad support for the ongoing development” of a wind energy industry in southern New Jersey, said Andrew Saporito, CEO of SJPC.

Education and training related to the offshore wind industry are also seeing an injection of new funding. NJEDA recently granted Atlantic Cape Community College $3 million to establish a safety and sea survival training program and facility to prepare workers for jobs in the industry. A separate wind turbine tech training program will award $1 million to a community college to establish an offshore wind turbine technician training program. Newark’s New Jersey Institute of Technology and Ørsted established a 10-year, $1.5 million program to create new scholarship and offshore wind career development opportunities for NJIT students. In August, NJEDA and the NJBPU agreed to provide $7 million to support workforce training, education, and research programs for offshore wind.

Perhaps the greatest economic impact of the wind port will be felt in regional manufacturing. The port represents “an example of how offshore wind is helping to build a new U.S. manufacturing industry,” noted Madeline Urbish, a government affairs executive at Ørsted. While the port will at first support marshalling activities, said Sullivan, it also “has the potential for additional expansion to include collocated offshore wind manufacturing activities.”

Once in a Generation Opportunity

That potential is already being seen on the horizon. The terms of NJBPU’s recent awards to Atlantic Shores and Offshore Wind require each project to build a new facility for assembling nacelles—the housing for the components that convert mechanical energy into electrical energy—at the wind port. Atlantic Shores has partnered with MHI Vestas, a wind turbine company headquartered in Tokyo, while Ocean Wind will collaborate with GE Renewable Energy, to develop these manufacturing facilities.

Both projects also committed to acquire monopiles—part of the foundation of offshore wind installations—from the manufacturing facility now being built at the Port of Paulsboro, New Jersey. Work in Paulsboro is ongoing to build a $250 million complex that will turn out 100 monopiles per year, a level of production that will require 150,000 tons of steel annually, according to EEW, the German company developing the facility. Monopile assembly for the Ocean Wind 1 project will begin in 2023, while the six-building complex is scheduled to be fully operational in 2024, employing 500 workers.

Meanwhile, Ørsted, developer of the Ocean Wind project, is seeking permits to build an operations and maintenance facility in Atlantic City. The company wants to build an in-water and marine support facility, replace a failing bulkhead, install moorings and floating docks, and prepare the property to support cranes.

These developments, taken together, all support New Jersey’s bid to become “the epicenter of a new industry,” said NJBPU’s Fiordaliso, “a once-in-a-generation opportunity.”

Follow us on social media: