Solar power depends on the solar cell. Wind power, the wind turbine.

The key to the green hydrogen economy is a little-known machine with a name out of 1950s sci-fi — the electrolyzer. And after a century of obscurity, the electrolyzer’s moment has come.

The device uses electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. If that electricity comes from wind turbines, solar panels or a nuclear reactor, the whole process gives off no greenhouse gases. Factories, power plants, even jet aircraft can then burn that hydrogen without warming the earth.

There are other ways to make hydrogen fuel, from natural gas or even coal. But the ways to do it carbon-free, with no emissions that need to be trapped and stored, rely on the electrolyzer.

“I don’t think people grasp what an electrolyzer is,” said Andy Marsh, chief executive officer of Plug Power Inc., which makes the devices. “It is the building block of green hydrogen.”

Unlike wind turbines and solar cells, electrolyzers aren’t immediately easy to understand. Larger ones can look like a jumble of tubes and pipes, while smaller, more modular versions are collections of electronics and machinery crammed into boxes the size of a shipping container or even a fridge.

Scientists discovered the process the electrolyzer employs — electrolysis — more than two centuries ago, and commercial electrolyzers hit the market in the 1920s. They were the main way to produce hydrogen until the 1960s, when a process using steam to strip hydrogen from natural gas supplanted them. Almost all of the hydrogen used around the globe today — in oil refineries, fertilizer plants and chemical facilities — comes from natural gas. Demand for electrolyzers dried up.

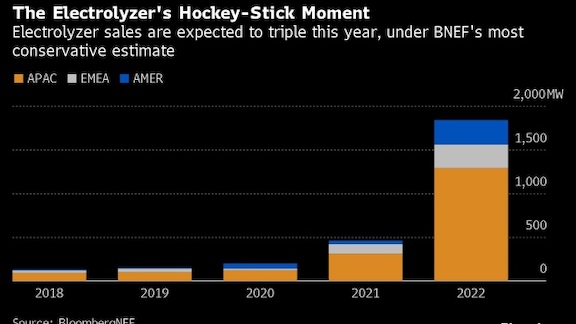

That has now changed — in just the last few years. Measured by the amount of power the machines consume, worldwide electrolyzer sales doubled from 200 megawatts in 2020 to 458 in 2021, according to BloombergNEF, a clean energy research group. They’re expected to triple this year, reaching anywhere from 1,839 megawatts to 2,464 megawatts, BNEF predicts. It may be the kind of hockey-stick moment solar power experienced a decade ago.

“It’s going to be difficult to supply all the demand,” said Amy Adams, vice president of fuel cell and hydrogen technologies at Cummins Inc., a veteran engine maker that has jumped into the business. “Can everybody scale up the supply base as fast as people would like?”

Even more explosive growth likely lies ahead. Electrolyzer “gigafactories,” each able to make enough electrolyzers in one year to use at least 1,000 megawatts of power, have been announced in Australia, China, India and Spain.

“When somebody says they’re going to build a gigafactory, they’re talking about in a year having more capacity than is installed in the world today,” said Patrick Molloy, a manager in the climate aligned industries program at the US-based RMI energy and climate think tank.

The amount of hydrogen each megawatt of electricity can produce varies, making comparisons between products and projects difficult. The most popular electrolyzer technology needs between 51 and 54-kilowatt hours of electricity, on average, to produce one kilogram of hydrogen, according to BNEF.

The underlying idea may be old, but there’s plenty of innovation. Electrolyzers come in three basic flavors — alkaline, proton-exchange membrane (PEM), and solid oxide — with different pros and cons. All involve water reacting with oppositely charged electrodes and an electrolyte, sometimes liquid, sometimes solid. Competitors are vying to perfect each technology. They’re paring down the use of such expensive catalysts as iridium and figuring out better ways to build a product that, until now, was largely assembled by hand.

Driving all of this is the need for a clean, carbon-free fuel. Solar and wind power now cost less than new fossil fuel generation in much of the world, but storing that electricity in bulk remains difficult and expensive. And some things, like steel mills and jet planes, can’t easily run on electricity. A molecule that can be produced, stored, shipped and used without pumping heat-trapping carbon into the atmosphere would work far better. Governments and companies worldwide are betting hydrogen will be that molecule.

“You need long-term energy storage, and you need it transported place to place,” said KR Sridhar, chief executive officer of Bloom Energy Corp. a veteran cleantech company now diving into the electrolyzer market. Large-scale batteries, he said, only provide energy for a few hours and aren’t portable. “You will not charge a big battery in Australia, ship it to Japan, discharge it and ship it back to Australia,” Sridhar said.

Hydrogen is the most common element in the universe. But here on Earth, it's typically bound together with oxygen, nitrogen, carbon or other elements. To use hydrogen as a fuel, it must be cleaved off of those compounds. That can be done in a dizzying array of ways, each represented by a specific shade on a constantly expanding color wheel. The dominant form of hydrogen today, pulled from natural gas, is “gray hydrogen.” Capture the CO₂ from that process, and it’s called “blue.” Strip the hydrogen from water using renewable power and an electrolyzer, and you get “green hydrogen.” Plug the electrolyzer into a nuclear plant, and it’s “pink.” Green hydrogen now costs far more than gray or blue: as much as $9.62 for a kilogram of green hydrogen, compared to $2.72 for blue, according to BNEF. But that likely won’t last. BNEF predicts that by 2030, green hydrogen will be cheaper than blue in every country the analysis service tracks.

For many hydrogen advocates, the electrolyzer is the missing piece to fulfill renewable power’s promise. It can take the excess electricity streaming from solar plants at noon and turn it into a fuel for use any time.

“That’s one of the things about electricity — we as consumers want it when we want it, and renewables don’t always work that way,” said Ian Russell, Bloom Energy’s director of development engineering.

Two of Bloom’s electrolyzers perch behind a low industrial building in Fremont, California, just up the freeway from Tesla Inc.’s original auto plant. Seven feet tall, their smooth, rounded covers pop out and up to reveal a mass of circuit boards, red and orange wiring, and a metal core that holds the “hot box” where water vapor separates into hydrogen and oxygen. The core runs between 750 and 800 degrees Celsius — a scorching 1,472 degrees Fahrenheit — but touch its exterior, and it feels warm. The only sound is the whir from a row of fans at top.

Bloom built its business on fuel cells, devices that generate electricity through an electrochemical reaction rather than combustion. Now the San Jose company is selling solid-oxide electrolyzers using most of the same technology, but in reverse. Hydrogen fuel cells combine hydrogen and oxygen into water as they produce power — electrolyzers do the opposite. They’re almost mirror images of each other.

“We’re building on our track record of fuel cells,” Russell said. “The manufacturing technologies, the field service program we have in place, the global supply chain — we already know how to do this.”

Plug Power also started with fuel cells before adding electrolyzers, and several competitors sell both. Cummins in 2019 spent $290 million to buy Hydrogenics Corp. for its fuel cells, thinking they could help decarbonize Cummins’s customers in mining and heavy transportation. But Hydrogenics had also developed electrolyzers, and now those look like the better business, said Managing Director Alex Savelli.

“We came to realize the electrolyzer opportunity is probably as big if not bigger, and probably will happen sooner, than the fuel cell,” he said. “Sometimes, it’s OK to get lucky.”

Each type of electrolyzer has its selling points. Alkaline electrolyzers, for example, tend to be the least expensive and have become the technology of choice for Chinese manufacturers. They’re trying to undercut their global competitors on price — just as happened with solar cells a decade ago — and BNEF reports that Chinese alkaline electrolyzers currently cost 73% less than comparable units made in the West. PEM technology uses more rare metals and costs more, but it can start faster than alkaline, something worth considering if the power source is as variable as the sun and the wind.

Hydrogen has become a priority for the Chinese government, and electrolyzers are a big part of the push. Electrolyzer deliveries there may top 1,600 megawatts this year, mostly on orders from state-owned businesses such as oil and gas giants Sinopec and CNPC, as well as high-emitting companies like coal-based chemical company Ningxia Baofeng Energy Group. If anything, demand is rising faster than production. And the companies making the machines — including one of the world’s largest solar manufacturers, Longi Green Energy — don’t want to limit themselves to the Chinese market.

“It’s quite difficult to order electrolyzers now,” said Mao Zongqiang, a professor at the Institute of Nuclear and New Energy Technology at Tsinghua University in Beijing. “The supply can’t meet the demand.”

The customers could, in the end, span many industries. Oil companies need hydrogen for their refineries, where it helps lower the sulfur content of fuel, although many have their own way of producing it from their own natural gas. But semiconductor and LED factories use hydrogen, too, and could benefit from on-site production. Electrolyzers would provide that. Owners of solar plants and wind farms may want to add electrolyzers, just as they’re adding batteries to their projects today.

“We’re just at the beginning of where this industry’s going,” said Ole Hoefelmann, general manager of Plug Power’s electrolyzer business.

Follow us on social media: