At around 3 a.m. on a cold and misty night in November 2020, a Molotov cocktail crashed through a downstairs window of a two-story brick house on the outskirts of the Dutch town of Hedel.

The shattering noise awoke Henri Seepers, who lived there with his brother Jan-Willem. Moments later a blast from a second explosive jolted him into a panic. He jumped out his upstairs window. Neighbors assured him his brother had also gotten out, and that his two German shepherd dogs, Cinda and Tessa, were safe.

It was only then that Seepers, bewildered and barefoot in a t-shirt and boxers, realized he was bleeding. Glass was lodged in his arms and head, and he’d broken his right wrist. He stood stunned as flames turned his home into a charred shell that night.

“Everything was blown away,” he recalled in an interview.

The Seepers were victims of a plot made possible by three overlapping forces: a booming cocaine trade in Europe, improvements to high-speed global shipping routes and increased demand for goods from Latin America.

Police and prosecutors traced the incident back to May 2019, when managers at a major fruit importer called De Groot Fresh Group discovered 400 kilograms of cocaine in a shipment of bananas from Latin America and turned the stash over to police. Authorities acknowledge they did not investigate who the drugs originally belonged to. Instead they focused on what came next: Extortionists threatened the family that owns the company, demanding reimbursement for the cocaine through cash and Bitcoin. When the De Groots didn’t pay, they unleashed a string of attacks — including eight with fire or explosives and four shootings — at houses of people with ties to the company. That included the Seepers brothers, who had worked in the warehouse.

The threats and attacks persisted for two years until police arrested the perpetrators, leading to the convictions of 12 men. Prosecutors alleged that the ringleader had found out about the stash and portrayed himself as a trafficker to exploit people’s fears about organized crime for a payday. The ringleader tried unsuccessfully to claim he was too busy running drugs elsewhere to mastermind an extortion plot. In September a court sentenced him to almost 20 years in prison.

Hedel is a quiet agricultural hamlet dotted with apple, pear and plum orchards. It sits in a municipality of the Netherlands called Maasdriel, which takes its name from the Maas River, the navigable waterway that winds from France to the Netherlands before emptying into the North Sea. The terror that peaked on the night the Seepers’ home was bombed led some locals to wryly give their home another name: “Palermo-on-the-Maas,” a nod to the capital of Sicily and its Mafia.

By virtue of a burgeoning trade in Latin American goods, the heartland of Europe has become a violent terminus for the international drug trade. Maasdriel is only one stark example of the dangers posed by the organized crime organizations that preside over the illicit commerce.

Latin America is experiencing history’s largest boom in cocaine production. And record quantities of it are landing in Europe, the world’s second largest market for the drug after North America, according to United Nations figures. At the heart of this crisis for law enforcement is a nagging question. How can police stanch the flow of cocaine into the continent without upending global shipping, one of its most important and powerful industries?

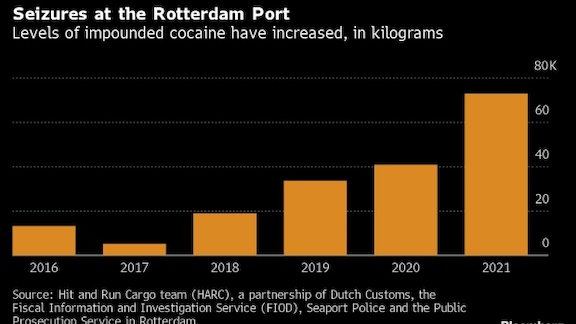

Last year, European Union authorities seized more than 240 tons of cocaine, triple the amount in 2016, according to a preliminary partial tally by the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), based in Lisbon. Most of that arrived not in human drug mules or private jets or yachts, but on the commercial container ships that serve as the lifeblood of the region’s economy, according to the center.

Most of it arrives in Rotterdam and Antwerp, the two biggest ports in Europe. It often comes in ships laden with fresh fruit and vegetables from Latin America, commodities that have grown in popularity as affluent consumers from Frankfurt to Paris demand year-round access to products once deemed seasonal. As Bloomberg Businessweek reported last week, organized criminal gangs have figured out how to hijack this logistics chain, moving large loads of narcotics along a maritime superhighway stretching across the Atlantic Ocean with the same speed and efficiency of major corporations.

European authorities are now grappling with not only the threat of increased drug addiction in cities across the continent — EMCDDA found an increase in people seeking first-time treatment for cocaine use in 14 countries from 2014 to 2020 — but also the cocaine boom’s attendant terror.

Authorities have made multiple cross-border busts in the last few weeks alone. On Nov. 25, Europol said one roundup nabbed 44 people suspected of belonging to one of the EU’s “most dangerous” criminal networks, which operated in Lithuania, Latvia, the Czech Republic, Poland, France, Germany and the Slovak Republic. A few days later, Europol said another investigation into criminals “flooding Europe with cocaine” led to arrests of 49 people including “drugpins” who had formed “a ‘super cartel’ which controlled around one third of the cocaine trade in Europe.” Most of the cocaine landing on the continent originates in Latin America and is the product of increasing collaboration between Europe-based criminal networks and Latin American cartels, according to a recent joint analysis from Europol and the US Drug Enforcement Administration.

In the Netherlands, the extortion campaign coincided with a string of chilling incidents that had already unnerved citizens, including two assassinations: the shootings in 2021 of crime reporter Peter R. de Vries, and in 2019 of lawyer Derk Wiersum, who was representing a witness in a trial for drug-related killings.

Such high-profile violence aside, the drug economy doesn’t necessarily mean daily life is less safe for most people. Netherlands national police statistics show crime is falling, with the number of reported incidents down 23% from 2016 to 2021, including violent crimes such as murder down by a quarter. But in places like Maasdriel and around the port of Rotterdam, the presence of organized drug crime has created a pernicious sense of fear. In February, a prominent prosecutor presented haunting photos in court of torture chambers allegedly built by drug gangs. The seven soundproofed chambers, found by police in 2020, had been constructed in shipping containers.

Latin America is the ideal greenhouse. Unlike in northern climates, farmers there can grow just about anything almost year-round — cherries, grapes, even more exotic fare like cherimoya or pitahaya. But historically, getting fresh goods from the Pacific coast to the rest of the world was hampered by a lack of infrastructure, such as good roads, refrigerated packing warehouses and modern ports.

Governments in Peru, Ecuador and Colombia began to privatize their state-run ports in the early 2000s, bringing in some of the world’s most successful logistics companies as partners. Around the same time, free-trade agreements with Europe and the US resulted in better terms for farmers, opening access to more markets.

Shipping companies descended on the region, introducing new technologies such as controlled-atmosphere refrigerated containers that allowed avocados and bananas to ripen more slowly during transit. In Peru alone, fruit exports to Europe nearly doubled over four years ending in 2021, according to Ricardo Limo, deputy director for exporting development for Peru’s Export and Tourism Promotion Agency.

Much of the cocaine that has contributed to the boom has hitched a ride in the same refrigerated containers.

North America remains the largest cocaine market in the world, though demand in the US has become relatively flat, said Antoine Vella, a cocaine research officer at the UN Office on Drugs and Crime. Meanwhile, in western and central Europe demand has increased, and put it almost on par with the US, Vella said.

The consumption patterns in part reflect price differences. The US price for a gram of cocaine has increased by more than 40% over the past decade to $120, according to UNODC data. But during that same time, some places in Europe where supply has increased have seen price decreases of as much as 10%, to below $60 a gram. With a gram yielding a half-dozen lines of cocaine, one snort can cost less than a cocktail in Rotterdam. And the average purity of cocaine on European streets has risen to more than 60%, from 37% in 2010. A recent report by the EU’s drug monitoring center cited rising use of the drug, including crack cocaine in a small but growing number of European countries. “Cocaine is now playing a more significant role in drug-related health problems in Europe,” the report said.

Those bargain basement prices in Europe are in turn related to traffickers apparently realizing that the most effective way to move tons of cocaine across the Atlantic was to insert themselves into shipping companies’ established networks.

Traffickers might bribe someone to load drugs at inland logistics points, for example, then pay Latin American customs officials to look the other way. Once a cocaine-laden container crosses the Atlantic, local gangs specialize in extracting the drugs from containers arriving in Antwerp or Rotterdam, for cash or a cut of the load. They have also bribed or coerced law enforcement officials and shipping company employees to help, court records there show. When US investigators conducted a $1 billion drug bust of a commercial ship called the MSC Gayane in 2019, they discovered that the traffickers had infiltrated the crew onboard the ship, allowing them to pull off an inside job.

“The supply chain became a lot more efficient,” said the UN’s Vella. “It used to be a big hurdle for organized crime groups to get quantities of cocaine across the ocean to Europe.” Container ships “are a big facilitating factor,” he said.

Shipments of fresh produce give drug smugglers an even bigger advantage, said Laurent Laniel, the chief scientific analyst at the EU’s drug monitoring center. “Authorities need to be quick because of course they are perishable products,” Laniel said, putting officials under pressure to limit their interference with such cargo.

Or as the head of Belgium customs, Kristian Vanderwaeren, put it: “The politics are that the trade should go smoothly.”

Ahmed Aboutaleb, an immigrant from Morocco and a former journalist, took office as the mayor of Rotterdam in 2009, just in time to watch the city become ground zero for the European cocaine trade.

“There is continuous pressure from this criminal underworld,” Aboutaleb said in an interview.

A tour through a Rotterdam neighborhood showed what Aboutaleb meant: Not junkies in the streets or bodies hanging from bridges, but unexplained wealth and the normalcy of drug traffic in daily life — more Miami in the 1980s than the Mexican north of the past decade. City officials pointed out signs of potential money laundering, which they said they had uncovered via a community outreach program that tracks commercial activity block by block. On one corner, a restaurant with no diners gleamed with fresh paint and colored glass after its proprietor had renovated the historic façade despite not owning the building. Down a broad boulevard, clusters of gold and jewelry shops were similarly empty, including one that had changed ownership several times in recent years. They also singled out a strip of garages with BMWs and Audis parked in the driveways. Body shop workers have installed secret compartments in the cars for smugglers to move drugs from the Netherlands and onward through the European supply chain, the officials said.

Aboutaleb has recommended more police collaboration with Latin American counterparts and more aggressive scrutiny of drug-related money laundering. He’s also called on customs authorities to search more containers carrying fruit from Latin America.

Fewer than 2 percent of shipping containers are inspected globally, according to the UNODC, making the hunt for cocaine a nearly impossible task. Shipping companies and government officials warn that more searches could translate into higher prices — a sensitive prospect amid the highest rates of inflation in a generation.

Shipping firms could do more to prevent smuggling without disrupting supply chains, Aboutaleb said, suggesting for example that they adopt more sophisticated anti-smuggling technology. “Money is not the big issue,” he said. “The shipping lines are making tremendous amounts of money.”

Aboutaleb worries how the drug trade has gripped a generation of young people. The legitimate salaries they earn as carpenters or shop owners pale in comparison to the money they can make fetching suitcases of cocaine from shipping containers or driving them from the harbor.

Some residents take measures to protect themselves from the drug underworld. In Rotterdam, the city officials who gave the neighborhood tour said it was crucial for some municipal workers to keep their names and duties private so that criminals can’t find and threaten them. “It’s hard if someone says, ‘I know where your daughter goes to school, just make sure this ship container gets out,’” said one official, who as a matter of city policy could only be identified as a spokesperson for Rotterdam’s Department of Safety.

Back in Maasdriel, a man who defiantly said he wasn’t afraid to live in what he called “Palermo-on-the-Maas,” ultimately declined to be identified by more than a single initial, “W.” “I don’t want the mafia at my door,” he said.

De Groot built its fortune on Latin American fruit. The business began before World War II, wholesaling local Maasdriel-area produce, but it was in the 1970s that Marius de Groot became the first Dutch trader to independently import bananas, according to the company’s history. He became known as Don Mario, a moniker which De Groot uses for its banana brand.

As has been the case with other fruit firms, De Groot started finding cocaine in its imports in recent years — at least twice before the big haul. Some Dutch fruit companies have been busted for being fronts for smugglers, according to court records. But De Groot has a policy of alerting the authorities.

The threats to the De Groots began soon after the company turned over the 400-kilogram stash to police. The first came in a text message sent May 26, 2019, to William de Groot, who had run the company with his brother, Ben. “WE HOLD YOU AND BEN PERSONALLY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LOSS OF OUR TRADE. YOU WILL GET A FINE OF 1.2 MILLION EUROS. WE NOW KNOW A LOT ABOUT YOUR FAMILY. YOU GET 3 DAYS TO DECIDE. IF THERE IS NO PAYMENT WE WILL LIQUIDATE ANY EMPLOYEE,” read the translated message, according to the court file.

William de Groot then got a message from another number: “If you screw us, you risk your daughter’s life.” The company didn’t pay.

On Jan. 12, 2020, around 11:47 p.m., a man carrying an envelope approached an apartment building where a member of the De Groot clan lived in Kerkdriel, Maasdriel’s municipal seat. Inside the envelope was a condolence card that read, “Warning!! The next card is for your family,” court records show. Surveillance video footage captured an image of the man making a throwing movement and then running away with his hands over his ears. He’d tossed a grenade, though it didn’t explode.

It was just the first of 16 attacks and attempted attacks on houses related to the attempted extortion, stretching until June 2021, court records show. Large-scale security measures, including personal protection for some individuals, nighttime checks on the A2 highway, and sealing off the entire surrounding district, called the Bommelerwaard, failed to prevent the assaults, prosecutors later told a court.

The main suspect, a 37-year-old who can only be identified as Ali G. under Dutch law, ordered several of the attacks from a Rotterdam prison after his arrest in January 2021, passing instructions via fellow inmates to collaborators on the outside, according to the court sentence. Prosecutors accused him of using promises of cash and cocaine to recruit foot soldiers from Amsterdam and around his hometown, Bussum, a commuter town 25 minutes by train southeast of the capital.

Police suspect he knew where to look for targets because prosecutors had mistakenly included a list of current and former De Groot workers in a court filing — an oversight for which the Dutch public prosecutor’s office publicly apologized. Brothers Henri and Jan-Willem Seepers were on that list.

Henri had worked on the cold side of the warehouse, while his brother worked on the warm side, handling bananas and pineapples, Henri said in an interview standing next to the foundations of what was once the family home. During the interview Henri, who stands a burly six feet six inches, visibly flinched when a white delivery van slowed down in front of the property. He later explained he’s suffering from post-traumatic stress.

Both he and his brother had already left De Groot when their house was attacked, he said. Henri, who’d started a new career as a DJ, got his first taste of trouble on a Sunday in June 2020 when he chased off a van with Belgian license plates that had been staking them out all day. On a Saturday in September 2020, a car out front honked its horn until Henri came out — and then a man in the car pointed menacingly at him before speeding off. Attacks on homes in the surrounding towns followed — breaking windows, scorching a front door, and damaging a parked car, but never coming close to killing someone. Then, in the early hours of Nov. 25, 2020, came the firebombing.

The investigation that followed used cellphone location tracing and intercepted communications to connect suspects to the events, leading to arrests and convictions, which are subject to appeal. On Sept. 27 this year, a court in Arnhem handed Ali G. the nearly two-decade prison sentence.

To many in town, the sentence meant the troubles were over and it was time to move on. A lawyer for De Groot, Taco van der Dussen, said his client “wants to ‘lay low,’” and that he and they were declining to comment. Maasdriel Mayor Henny van Kooten also declined to be interviewed for this story. “It’s time to put the incident behind us,” spokeswoman Lieke Lataster said.

Still, the fear lingers. Willy Bruninx, 82, a retired engineer, said the buzz of helicopters that had started over the area a few years ago, presumably on anti-drug missions, hasn’t stopped. Sander Hooymans, 33, who owns a phone shop there, said the military police have stopped guarding De Groot, but the cameras remain. “You just need to know where to look,” he said.

Henri Seepers and his brother are preparing to rebuild their old house with insurance money. In the meantime they have been living in a mobile home they set up behind the garage. For almost two years, Henri said, he slept fully clothed, in case he needed to flee again. In the temporary home — where one space serves as a combined kitchen, dining and living room — there are signs of his continued vigilance. A video monitor on a shelf glows 24-hours-a-day, showing the views from security cameras he’s placed around the property. At the doorway to the closet-sized alcove where he sleeps, a red fire extinguisher stands sentry. Just in case.

Follow us on social media: